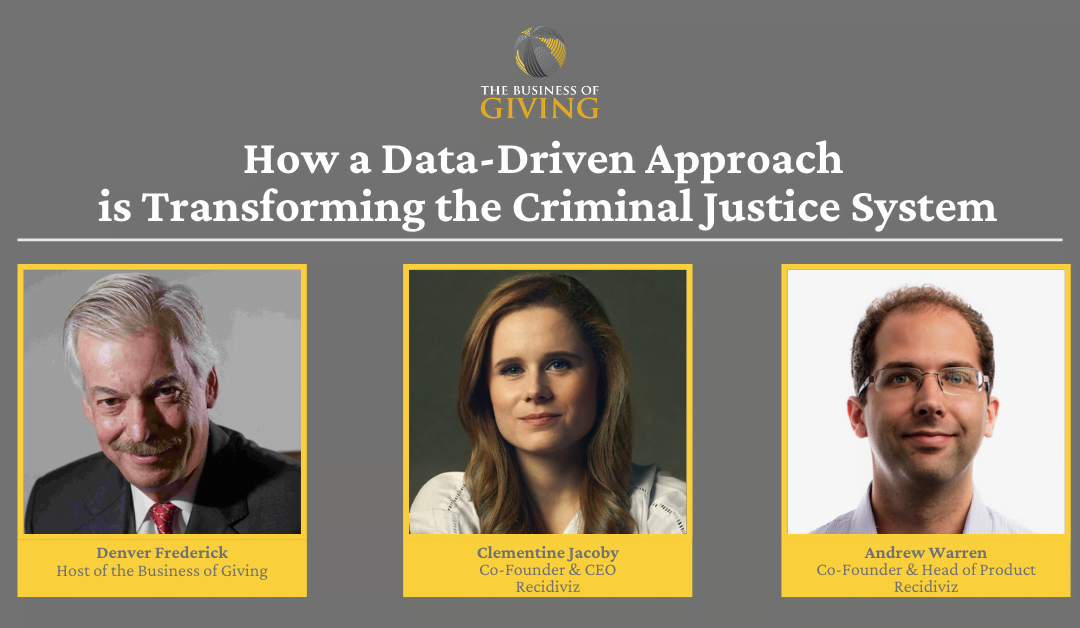

The following is a conversation with CEO Clementine Jacoby and Head of Product Andrew Warren of Recidiviz, and Denver Frederick, the Host of The Business of Giving.

Clementine Jacoby & Andrew Warren of Recidiviz

Denver: The United States comprises less than 5% of the world’s population, but close to 25% of the world’s prison population. Part of the problem is that there’s a nationwide lack of uniformity in collecting and sharing data in the criminal justice system. It’s a Tower of Babel of sorts, which leads to inefficiency and poor decision-making.

An organization that has made remarkable progress in addressing this seemingly intractable challenge is Recidiviz, and it’s a pleasure to have with us its co-founders, CEO Clementine Jacoby and Head of Product Andrew Warren.

Welcome to The Business of Giving, Clementine and Andrew!

Clementine: Thank you for having us. Good to be here.

Andrew: Thanks.

Denver: Let me start with you, Clementine. I just alluded to the fact that the incarceration rate in the United States is the highest in the world on a per capita basis, well ahead of El Salvador, which ranks second. How did that come to be?

Clementine: It’s a great question. And one thing I would add to that, just to put it in context, is that our incarceration rates would actually have to drop about 75% just to come in line with the international average, so not just to pull ahead of the pack, but just to kind of get into the middle.

It was not certainly always like that until about the 1970s. US incarceration rates were about on par with other European democracies, and between then and 1985, the population nearly tripled. And a lot of that was to do with the war on drugs, with increasing lengths of sentences. There are a lot of problems with longer sentences. One is that you stay in longer, and the other is that when you get out, you have a harder time staying out. The United States also has an enormous number of collateral consequences that are applied when someone is released from prison. So that’s a big piece of the puzzle.

And then one other thing I would call out, not as though it’s possible to name all of the reasons, but one really big piece of this that I think is a bit hidden or not often thought about is supervision. So in the United States, probation and parole populations are much, much larger than they are in other places in the world. We have between 4 million and 5 million people on supervision. And often, for a very long time… you can get eight years of probation for a DUI in some places. And it’s pretty hard to stay out of prison when you are on probation for eight years. A minor infraction can really lead to a prison sentence that, again, is quite long. And so, it becomes sort of a revolving door of incarceration that supervision is a big part of.

Denver: Yes. It really follows you around.

Andrew, anytime I’ve ever wanted to understand an organization better, I have always asked somebody about their founding story. Your founding story is relatively new. Tell us how this all came to be.

Andrew: There’s a lot of different places where we could probably start with that because it kind of came together over a couple of different years when Clem and I were working, along with Josh, more on just consumer tech.

One of the pieces that I think was actually instrumental to putting us on this path was there’s a group called Convergence that pulls together different groups from around an ecosystem that seems to have large intractable problems and gets them in a room. And we were invited to one of these as we were just starting to nibble around the edges of criminal justice, just starting to put out some open-source tools, some things that might help

And we go into this room, and there’s about 20 people there. It’s advocacy groups from the right and from the left. It’s heads of corrections of states in the US. It’s heads of private prison companies. It’s think tank folks from the right and the left. And all of these folks were in shocking agreement. It was just so strange to sit there in the middle of them and have them start off with, “I think we all know that mass incarceration in the US seems to be stemming mostly from a history of some race and drug-related issues.” And everyone is nodding. There’s no person in this room who disagrees with that statement.

And then they start going into “And I think we’ve talked through in our prior sessions how many things that we’re trying to try to figure out– how to unwind things and get back to a steady state that seems more reasonable,” and everyone in the room is nodding. And then they kind of turned more to us, which is very surprising as a couple of folks who have nothing to do with this ecosystem, and say, “You know, the main thing that we’ve identified so far is the blockers. We just don’t know what’s working and what’s not. There’s just not a clear picture from the data across the system of what’s actually happening.”

And so, it seems as though there’s a data problem that we need to solve before we can solve some of these other pieces that are the more larger and bigger lifts in many ways, but they’re being blocked by a lack of information. Some of my prior work had been on mobility and in looking in different areas of government technology, and areas where government can be helped by technology. In a lot of those areas, there just wasn’t a data problem. There wasn’t a technology problem at the end of the day. The problems came from somewhere else.

And so, I think that was a little bit of an interesting turning point for two reasons. One was, it became clearer and clearer to us the technology and the kinds of things that we work on could actually be helpful here in some way. And then two, out of that discussion, actually one of the heads of corrections, Leann Bertsch, raised her hand and said, “I think we should use North Dakota as a place to start trying to tackle this particular problem because I think that we have a leadership team that’s supportive of that. And I think that we’re actually able to try a few different things and see kind of whether we can get a better picture of what’s going on.”

And so, based on that, we actually went into the first state that we started working with. And it was very shortly after that that we actually quit our jobs in large tech and moved into starting to hire folks to start working on this full-time.

Denver: That’s a wonderful background story. Before we get into the data part of it, Clementine, let me ask you something about the lack of clarity and maybe the lack of clarity that I have around this issue. And that is this: What are prisons actually for?

Clementine: You could be forgiven for not knowing the answer to that question. I think one of the things that is so interesting about the US criminal justice system is the lack of clarity on this question. I think there are kind of three hypotheses that you might have.

So one is that prisons are for punishment, that they’re for exacting a punishment for a crime. Another is that they’re for rehabilitation, which is in large part, if you look at how much of the admission stream to prisons in the United States is for substance use and mental-health-related issues, you’ve got to believe that prisons are the right place to do rehabilitation. And I think that the data on that is pretty resounding that they are not. So that’s an interesting theory. And then the third is incapacitation. You might just believe that someone is a danger to society, and you don’t know how else to fix the problem except for incapacitation.

But I think it’s powerful that you asked this question because one of the things that I think the average American can do to help with criminal justice reform is just get clarity on that question within themselves. So those are three very different goals. It’s not totally surprising that when we ask one building to do all three of them, that it’s not very successful at doing any of them. And one of the things that I think is so powerful about what corrections directors are trying to do with our data or with their own data that we help them with is to clarify what their goals are and then track them over time, and that that exercise alone actually lends a lot of progress.

Recidivism is the tendency of someone to re-offend. It could be defined as someone who committed a crime who commits a crime again. Or much more often, it’s defined as someone who’s been in prison, who leaves prison, and then comes back to prison.

Denver: I can relate to that. Any time I try to multitask and do three things at once, it’s a disaster. Nothing gets done. Tell us a little bit about recidivism. And you have said that it’s an important concept, but it’s a lousy metric. Explain that to us.

Clementine: I think my position on recidivism is that it’s an important idea, like you say. So recidivism is the tendency of someone to re-offend. So it could be defined as someone who committed a crime who commits a crime again. Or much more often, it’s defined as someone who’s been in prison, who leaves prison, and then comes back to prison. But therein lies the issue.

It’s an important concept because when we’re thinking about what works, we want to reduce those things. The issue is that when you’re a metric, your only job is to mean the same thing in every context. And on that measure, recidivism fails. It means many different things to many different people. It means different things in terms of content, and it’s also measured in different ways…. Sometimes over six months or three years or one year. Sometimes a re-arrest counts. Sometimes you have to go all the way back to prison to become a recidivist.

And so, this was a problem that may sound boring to you, but that fascinated us at the beginning… just trying to get clarity on this so that we could actually compare outcomes across programs, compare outcomes across states, and begin to get a sense of what was working.

Because every part of the system is kind of managed by a separate entity and all of them have their own data silos, you don’t have a complete picture of what’s actually happening or what’s working to improve outcomes, or not working as the case may be.

Denver: Language is so important, it really is, in having a common understanding.

So, Andrew, getting back to the data, I guess we have about what… 18,000 police departments and maybe 16,000 courts, and I don’t know, 600-, 700-, 800 prisons. They’re not communicating with one another. They weren’t. What questions were we unable to answer about our justice system because of that lack of communication?

Andrew: It’s tough to know where to start candidly. The reality is the system isn’t communicating with itself. It’s not just what we can’t know. So, in terms of things that we don’t know, we don’t know how many people are in jail on any given day. We don’t know which states are actually doing better or worse at rehabilitating people, for instance, based on what Clem just mentioned.

But the larger issue that I think we’ve seen as we started to work in this space is just that the other parts of the system don’t know what each other are doing at the end of the day. So the prison system has no idea how many people are in jail, which seems important if you want to know how many seats you might need in the prison system at a later date, even if you’re just thinking of it as a pipeline of sorts. The court system doesn’t have any visibility into whether the people who they send to prison on these very long sentences end up actually doing better or worse as a result of those sentences because they don’t see to the other end of the process. They don’t see what happens to people on probation. They don’t see what happens to people on parole.

And so, because every part of the system is kind of managed by a separate entity and all of them have their own data silos, you don’t have a complete picture of what’s actually happening or what’s working to improve outcomes, or not working as the case may be.

Denver: But how do you address that? And I’m going to say this, Andrew, in the context of I’ve spent my whole life dealing with institutions and systems which don’t communicate with one another. They’re in silos. How do you get them to cooperate and share their data? That is really, for me, the million-dollar question.

Andrew: Part of it is helping to highlight what that data can actually do. I think one of the things that’s most important is that you need to have a feedback loop that people are actually using to see, “OK, I need this data for operational reasons. This is something that I need to be able to see.”

And one of the things that we’ve found as we’ve gone into states is it’s very similar to a situation where you have like a CEO of a company who’s trying to manage an $8 billion organization, and they have no metrics whatsoever on what’s actually happening in that organization. They have no way of knowing how sales are going. They have no way of doing… knowing what the costs are at different parts of the organization. And there’s no one looking at the entire entity at the end of the day.

So, one of the things that we try to do is we try to go in and stitch together data, or we just show what we’ve been able to do in stitching together data in other places. And as soon as you start getting even one group’s data into a place that starts to tell the story of what’s actually happening, that starts to show that picture, you start getting outreach from the other groups asking, “Can we plug our data into this, too?”

Because they see the value in understanding for themselves: How are my decisions as the parole board impacting the people in the system, the racial skew of the system, the outcomes of people once they get back into the community, as well as the public safety outcomes? How are my decisions as the court system doing the same?

And so, a lot of it is trying to get just the initial data sources that we can plug together in a way that people haven’t seen them before, that starts to tell the story of the outcomes.

Denver: And would I be right to assume, Andrew, that that data’s not as bad as sometimes we think it is? When we think about these legacy systems, and you think it’s just junk in/junk out, but it kind of indicates that some of this data is pretty darn good.

Andrew: You’re so right about that. It’s so true that a lot of states, when we first started talking to them, their initial reaction is: “I love all the idea of this, but the reality is I just don’t think our data is good enough. I don’t think we’re collecting enough.” And I think there’s a few different factors to that.

One is: I think government tends to believe that it’s just always behind the private sector in some way, shape or form on technology and data. But the other piece is there’s a tremendous amount being collected, and even where data is not being collected, there’s so much that you can do to stitch together the pieces that are there to start to show where the gaps are and what you can do with those.

Denver: Clementine, so how do you guys… how does Recidiviz work?

Clementine: I’ll answer that, but I’ll also just say that what you asked and what Andrew responded is so true. When we started doing this work, people asked us all the time how we would possibly get a state to let us build these tools. And it’s been the opposite of that problem. I think that people who are leading correction systems, I think law enforcement, the courts — they’re the ones who want to know the very most which of the things that they’re trying are working. And I think data is one way to put them in a position to actually hit their goals and to enact their vision. Everyone… public servants get into the work to produce good outcomes. They want to be there.

And so, we’ve had the opposite experience. We have seen no resistance to people wanting data. They’ve been the ones who have asked for it and really who have given us, I would say, all of the ideas for every one of our products.

Denver: That’s fantastic. And if I can just add to that, too. Even the way you guys have tackled this… we have these assumptions, and we live by those assumptions. One assumption we just talked about was the data is no good and they would never share it. The other assumption is: Who in their right mind would tackle this problem? It seems intractable. You can’t make a dent, and once you get into it, we sometimes surprise ourselves that you can… as you have… made remarkable progress.

Clementine: This is another myth that certainly took me a while to be disabused of, but in tech, gov tech is seen as being one of the hardest, slowest slogs you can sign up for. And that has so not been our experience. If anything, I think the leaders in the systems that we’re working in and their staff have been the ones generating the ideas, working with the designers to design the tools, coming up with sort of the next place where the data can help.

So, to answer your question of what Recidiviz does in the same breath, when we first come in, we start with the staff. We start with these parole officers who are overwhelmed, who are supervising 110 people at a time, and we say, “We’re going to gather together the data on who’s got housing, who’s employed, who has treatment needs, and we’re going to surface that to you so that you can see where to direct your attention.” We start there, and we help them basically identify folks who can get off of supervision early, folks who really, really need their attention, and separate those two groups out.

As that starts to improve outcomes, then we say like, “Well, let’s make a leadership review to see how this is looking across the state. Let’s see what the outliers are. Let’s see where we’re getting really good outcomes and what we can learn from that.” But then, as soon as we started doing that work, leaders started asking, “Well, what can this data do to help us motivate legislation? Or what can it do to help us track the impact of legislation that was just passed?”

And so, those are kind of the three main areas that Recidiviz started its work in, which then led to: let’s make some of this data public. And so now, we have live dashboards powered by our platform that the states can use to sort of release their data, that’s being refreshed nightly, that answers some of those questions Andrew mentioned early on that weren’t answerable before.

And so, I guess to me, the experience has been that government has been the one pulling us along and pulling us forward, and that we’ve just been trying to keep up with them/keep our ears open. There are definitely challenges, no doubt. I think there are good, good reasons for government in many cases to move methodically and even to move slowly. They’re dealing with people’s lives. These are really, really serious and high-responsibility jobs. And so, that is certainly true, but to the extent that we come in and say, “Here’s an experimentation platform; what do you want to try to improve outcomes? We will let you know if it’s working,” they are very all game for that.

Tech likes to talk about how we work at scale and how we impact millions of lives. Government is the original scale and the original impacts millions of lives. And in my view, if you want to have impact with technology, you do gov tech. Making the government 1% better, getting services to 1% more people, improving outcomes by 1% at statewide scale, at national scale, at regional scale– that’s the way to have impact with technology, I think.

Denver: And contained in your answer, Clem, is you disabuse another myth, which is that public service employees are just there for the ride. And I go to the Partnership for Public Service event every year where they honor federal employees at that particular thing. And these are some of the most dedicated, innovative people that I’ve ever come across. I just love going to that event down in Washington. But we have this sense of: “Oh, you’re just there. You have no motive. You have no incentive. You’re just kind of showing up and punching the time clock.” And really, nothing could be further from the truth.

Clementine: Nothing could be less true. Tech likes to talk about how we work at scale and how we impact millions of lives. Government is the original scale and the original impacts millions of lives. And in my view, if you want to have impact with technology, you do gov tech. Making the government 1% better, getting services to 1% more people, improving outcomes by 1% at statewide scale, at national scale, at regional scale– that’s the way to have impact with technology, I think.

Denver: Andrew, you know, we’ve had the pandemic, and there has been this effort to de-carcerate to avoid COVID-19 within the system. How were you able to help states and localities do that efficiently and effectively?

Andrew: This was actually a really interesting moment for us. There were a few different things that kind of happened at once.

We had some kind of personal tragedies on the Recidiviz team around that time period. We then also had… the COVID, as you remember, as it started in the US, it was a bit of a confusing time. It wasn’t clear. There was kind of a quick two-week period in which suddenly it went from, “It might be an international thing” to “Oh no. It’s very much here.”

And so, there were a few things that happened. We lost our office. We moved everyone out of the office very quickly. We kind of sent everyone home. Some folks started to have family members who started to contract COVID, and that was the first that hit our team. But as this was happening, the states started reaching out to us that we had been working with and said, “We’re not really getting a very clear picture of how this is likely to impact the incarceral system. Do you have any data? Have you seen any metrics? Do you guys have any modeling that might help us to understand what’s actually likely to happen if the disease gets behind the walls?” Which was kind of the mentality at the time of: If it gets behind the wall, which the walls are very tall and so probably not. But if it gets behind the walls, what’s likely to happen?

And so, we actually started pulling people off of other projects to ask them to take a look at this and to try to figure that out. And to be honest, the amount of data available was very, very poor. The only comparisons we had for people kind of in tight-knit spaces similar to this, as comparison points, were cruise ships and San Quentin data from the 1918 Spanish flu. So there was very little to work on. But we started to reach out to some of the epidemiologists who thankfully– even though they were also very busy– it started at Stanford and Yale, started taking off time to help us to put together a model of this.

And I think we put together the first model within a few days, and we put it out on the other side of a weekend. Within a day of that and with the help of groups like CSG and a couple of others who helped to push it out there, 49 of the 50 States had started to take a look at that model and started to use it to take a look at what might happen within their systems. Within a week of that, we were deluged with requests to clarify and to talk with folks, and to join meetings. We ended up working pretty closely with about 34 states as we continued to develop that model on helping them to understand what might happen within their system in particular.

And those states ended up — help me out of here, Clem — they ended up recommending at a rate of about 4X early releases of folks from the prison system, which is very overcrowded, just in case folks don’t realize that. A lot of prisons, 150% capacity, 200% capacity. Was that number right, Clem? Yes. So that ended up resulting in about 44,000 recommendations for early release for folks who are considered low risk and weren’t likely to actually affect public safety at all in the community.

And then what we were able to do after that I think was deemed a little bit more important because we started providing weekly reports to these departments of corrections that we worked with to do this. And several of them got those weekly reports showing them the impact of those folks in the community. And the result was actually very promising. These folks did not recidivate or have any new crime violations at a rate that was higher than anyone else being released at a normal time period.

Denver: So in looking back now, it’s over a year, what has been the impact of all that? And is there going to be anything from that that will inform how you go forward, even in times when there isn’t a pandemic?

Clementine: So I think that’s everything that we are focused on in 2021. So right now, prison populations are down. And moreover, we just ran a forced natural experiment. So it has been a terrible year to be in prison. It has been a terrible year to be running a correction system. You’ve been sandwiched between public health and public safety risks. It’s been a really, really tough time. And so I think there’s an imperative for us to learn from this.

And the interesting news is that it’s so rare in public policy for everything to change at once. It’s so rare for prison populations to drop 17% in about six months. And so, what Recidiviz is focused on is working with our state partners to see what happened, to understand which of the changes that we made maybe were beneficial.

So, many things were bad. For example, no one was able to visit prisons, and so people who were incarcerated haven’t been able to see their families in months. Some of them had to be in solitary confinement, not because of any of their behavior… just to slow the spread of the virus. But some things have actually, like in so many sectors I think, been discovered as innovations. So for example, in many places, we’ve been doing low-risk probation and parole by phone. And this is potentially a huge deal because today it’s really, really hard to be on probation or parole. You may have to leave your job in the middle of the day to drive to meet your parole officers. Similarly, it’s very hard to be a PO. You have to drive to meet all of your supervised folks. And so, phone might be a thing that could improve lives, could improve staff’s jobs, and could save money.

Similarly, we’ve been sending fewer people to prison for technical infractions. I think every state is interested in knowing what happened with that. Things that would have led to prison sentences a year ago have not been leading to prison sentences. And what has that meant and what has happened? How has all of this impacted racial disparities? How could it impact the amount of money that we spend on corrections going forward? Could that money be better spent elsewhere? For example, at the front end of the system, with substance use treatment or with mental health treatment. All of these are things that I think law enforcement and the courts and corrections all want to know the answers to.

So Recidiviz has been collecting data on this for the last year. We’re now very excitedly looking at the data, and I think the hope is just that we can move forward from COVID, having learned and discovered things that otherwise would have taken us 10 years to find or to slowly iterate towards.

Denver: That’s exactly what I was just thinking as you were talking there. So it’s most like you woke up, and it was 2030, and here you are just fast-forwarded into the future.

Clem, Andrew talked a little bit about North Dakota before, but let me ask you about another one of your initiatives that I’m really interested in, and that’s Spark. Tell us about the Spark Model.

Clementine: So Spark actually came about, in a way, out of COVID. So to explain this, I have to explain one thing which is that we have this model that was helping us model and forecast what would happen with COVID: How many staff would get sick? How many incarcerated people would get sick and hospitalized? And to do that, we had to model how people flowed through the criminal justice system.

And as we were doing this work with so many states, 34 States, we started getting questions about: “Well, what if I changed this policy? How would that impact my COVID numbers?” And we realized that, as we got more and more and more of these questions, that we should really be generalizing this model to support policy impact modeling as a whole. If we were to repeal mandatory minimums in the state of Virginia, what would that do to our prison population? How much money would it save to the state in the next five years? Or if we were to cap probation terms in California, similarly, how would that impact demographics? How would it impact costs?

And so that’s what Spark does. Spark is a totally free offering that Recidiviz has to the advocacy ecosystem. We are not advocates ourselves. We don’t champion any particular bill. Advocates come to us and they say, “This is a bill that we’re championing. Tell us, in a quantifiable way, what the impacts will be.” And then they take these memos, and they go have conversations with legislators and try to figure out if they can get this bill passed.

Similarly though, now, states do the same thing. So sentencing commissions may ask us to model a bill although often they’re better at modeling them than we are; so sometimes we can add less value there. Governor’s offices will ask us, DOCs will ask us, and it’s been a very cool way for us to be able to just democratize access to this kind of forecasting. We can’t always do a perfect job. Sometimes we’re up against pretty crappy public data. But like you mentioned earlier, I think so often, the data is better than we thought. So often, we assume that it’s not going to be possible, and then we dig into it, and it is. So that’s what Spark is doing.

Denver: I love Spark. Boy, that can have some incredible multiplier impacts in terms of really changing a lot of things.

Andrew, where can a team of software engineers have the most impact? Where do you look at where to go about scaling the work that you do?

Andrew: A team of software engineers in the context of criminal justice? In the context of…?

Denver: Criminal justice. And in terms of your work.

Andrew: I think there’s a few different pieces to that in my mind. One of them is simply trying to bring better approaches to data and data standards to government.

I think one of the things that we’ve seen over the last 20- or 30 years has been this tendency to have kind of the Silicon Valley-style of tech: Avoid government and instead have kind of a vendor ecosystem crop up that’s really focused on building everything once for exactly one customer, and then needing to make money off of that in recurring way over a lot of years. And the only way to do that is to do things like take ownership of that data and charge the state for access for it… to it. Or try to be very, very careful over not building any inter-operability so that these systems can talk to each other.

So I think one of the pieces would just be I think we tend to avoid — on the Silicon Valley and kind of big tech side — we tend to avoid working on gov tech for a lot of reasons, but especially gov tech that we worry might end up being used in ways that we’re concerned about, like things like criminal justice tends to put people off. But the reality is that’s all the more reason why there’s a lot of need for folks from the technology ecosystem to come in, not as folks who have better answers to any of these things, but as a new resource that can help the people who’ve been working for the last decade to actually unwind various significant problems in this space… to do so in a way that works much faster, much more easily.

The one thing that most of us overlook is that technology doesn’t tend to solve problems. It tends to make things more efficient.

Denver: Andrew, let me ask you a general question now, if I may. I talk to a lot of people on this program, and one of the things they constantly bring up to me is: how can they as a nonprofit organization become more digital, more technology-focused to increase their impact in the wake of the pandemic. Would you have any advice for those leaders of those organizations who are embarking on that journey right now?

Andrew: So I think that there’s a few different ways that I’d look at this. There’s naturally looking for… well, let me take a step back for a second. I think the one thing that most of us overlook is that technology doesn’t tend to solve problems. It tends to make things more efficient. And so often, the challenge that for instance we have in the criminal justice system is we don’t necessarily want to make it more efficient at all of the things that it does. We want to make it more efficient at actually rehabilitating people and getting them back out into the community in a safe way.

So, as another nonprofit, whether it’s in the criminal justice space or not, I’d first look at: What am I trying to achieve? And is it an efficiency game, in which case technology is well suited to those kinds of problems? Or is it something about a qualitative change or a cultural change that you’re trying to effect, in which case technology is usually not as well suited to that? Or at least it requires a lot more nuance to bringing to bear against the problem.

I think a lot of the pieces that nonprofits can use is it’s best to partner with an organization that has deep technological bones, so to speak, that can help guide you in kind of “Here’s how I’d approach this particular kind of problem. Here’s what’s feasible and what’s not.” Because it’s otherwise very difficult sometimes to tease apart what is something that could be done by a software engineer in an afternoon versus something that would take our team of researchers five years, especially at that moment with machine learning and some of the tools on the artificial intelligence side. There are kind of steep drop-offs in the waters at certain points, and there’s a lot of marketing out there that makes it seem as though everything is a panacea.

One of the things that’s so characteristic about the criminal justice system, both for the practitioners and for the people trying to help them, is its fragmentation. It’s such a fragmented system, and COVID did this really wild thing, which was that it focused everyone in that very dispersed ecosystem at once on the goal of reducing density in these facilities.

Denver: That’s actually really wonderful advice. Thank you.

Clementine, what’s it been like leading a relatively young organization through a crisis like this that we’re still experiencing? And do you think it’s informed your leadership, whether it’s the way you go about making decisions or solving problems out into the future?

Clementine: For sure. I think the thing that Recidiviz has tried to do in our decision-making is lean as hard as we can on domain experts, whether that be outside the criminal justice system or the practitioners themselves; and doing that during COVID has, of course, been harder. We haven’t been able to visit states, which is where we used to learn so much about what the needs were. We would ride around in cars with parole officers, and we would sit at headquarters and try to understand how they were using data today and what we could do. And all of that has been impossible during COVID.

At the same time, though, we’ve gone from working in a small number of four states to working in a lighter-weight way with 34 States, and now bringing our platform to seven. And so, we’ve had so much more diversity of input and so many more leaders with really compelling visions I think that we can accelerate. And so, I think it’s been a tradeoff for us in terms of where the input is coming from.

I think one of the great dangers of being a tech company trying to have social impact or trying to work in government, or trying to work on a problem with a really complicated history is just that you can get too confident and think that technology can solve things that it, in fact, can’t… which you hear Andrew talking about. And so it’s been critical for us to lean really heavily on the people who know what they’re talking about, and I think there’ve been pros and cons for that.

The other piece is just that we were a small team when we left the office. We were six people. We knew each other really well. We could all fit in a minivan. And now, we’re more like 35 people. And so, building that team remotely and making sure that everybody feels connected to the people that we’re trying to help, and knows what it’s like to be a corrections director, and has talked to parole officers and understands what it is that they’re trying to do — that has been a big piece of what we’re focused on.

And then I’ll say one more thing, which is just that the ecosystem has moved and changed. One of the things that’s so characteristic about the criminal justice system, both for the practitioners and for the people trying to help them, is its fragmentation. It’s such a fragmented system, and COVID did this really wild thing, which was that it focused everyone in that very dispersed ecosystem at once on the goal of reducing density in these facilities.

And so, you saw how much happened when that kind of focus came about, but it just dramatically changed the nature of the work. You had Libertarians and Progressives and religious communities all working alongside each other, alongside law enforcement and corrections and the public and this racial justice movement towards the same goal– potentially with different reasons. It was a very interesting time, and I think continues to be a very interesting time. And I think there’s a lot to say about hopefully what will come of that big experiment.

Recidiviz tends to see itself as an experimentation platform. If we can just take the good ideas and help people see whether or not they work, that’s victory.

Denver: And I gather it’s a really pivotal time, too, because what happens after this? What will occur when we get back to our so-called normal? Will this continue? Or do we tend to sort of fall back to the way we once were?

Clementine: Recidiviz tends to see itself as an experimentation platform. If we can just take the good ideas and help people see whether or not they work, that’s victory. And so, for us, COVID, this giant experiment, was a pretty big acceleration of, I think, all of the learning that we’re hoping can be fruitful for the system.

So I do. I think it’s a pivotal time, and I think what we do in 2021 will set the course for the next 10 years.

Denver: And I was saying to Andrew before, when you were talking about founding, I talked to a number of organizations and when their founding was based upon three or four different models that they experimented with, they have had a relatively easy time with COVID because it was in their DNA that we try out things. So when they had to try out some different things, it didn’t become as big a challenge.

Tell us about your website and the kind of information that people will find there, and where listeners can maybe become involved and help you guys continue this work.

Clementine: Sure. So our website is recidiviz.org. You can do a couple of things on our website. One, you can reach out to us. Recidiviz has tons of volunteers. Many of them have come from Google.org who, speaking of the pandemic, gave us a big lift when we were frantically trying to scale up. Lots of Google engineers spent lots of nights and weekends helping us. Another group called US Digital Response played a huge role as well. And so, that’s one of the things you can do is reach out and let us know if you’re interested in full-time roles in the space, or interested in volunteering.

Another piece is that you can check out the Spark work that we mentioned– our policy impact modeling and read about legislation that’s moving across the country.

Andrew, anything else that you would add to that?

Andrew: No, I think that’s a pretty good summary. One of the things that we’re looking to actually hopefully publish more of is some of the research that we’re actually doing in order to understand the sector because I think one of the things we can do as outsiders coming in is: we’re doing a lot of documenting what we’re finding in terms of how parole and probation and different folks work and how they’re motivated. And so, I hope that we’ll be able to share more of that soon.

Denver: You guys are a dynamic duo, and I want to thank you so much for being here today. And I hope maybe you can come back in a year or 18 months and give us an update in terms of all the work that you’ve been doing. It was a real pleasure to have you both on the program.

Clementine: We’d love to. Thanks Denver. Thanks for having us.

Listen to more The Business of Giving episodes for free here. Subscribe to our podcast channel on Spotify to get notified of new episodes. You can also follow us on Twitter, Instagram, and on Facebook.