The following is a conversation between General Robert Caslen and Dr. Michael Matthews, authors of The Character Edge: Leading and Winning with Integrity, and Denver Fredrick, the Host of The Business of Giving.

General Robert Caslen and Dr. Michael Matthews, Authors of The Character Edge

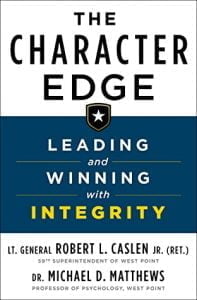

Denver: Character, the moral values, and habits of an individual is in the spotlight now more than perhaps at any other point in modern history. What is the role of character in successful leadership, and how do you build it in individuals and prospective leaders? Those questions are addressed in a wonderful new book titled The Character Edge: Leading and Winning with Integrity.

And with us now are its co-authors, General Robert Caslen, the 59th Superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point, who is now serving as the President of the University of South Carolina, and Dr. Michael Matthews, Professor of Engineering Psychology at the US Military Academy at West Point.

I’d like to welcome you both to The Business of Giving!

Mike: Glad to be here.

Robert: Thank you very much. It’s great to be with you, Denver.

…it is these enduring and consistent behaviors, beliefs, and actions and values that characterize that person’s approach to the world.

Denver: Let me start with you, Mike, by asking: What is character?

Mike: Well, you gave a good definition right at the top. I think you may have pulled that right out of our first chapter, maybe. But I just say it is these enduring and consistent behaviors, beliefs, and actions and values that characterize that person’s approach to the world. And they can be things like performance character, things that help you do better, like grit and determination and self-regulation. But there’s also the type of character attributes that have to do with your values as a human being — strengths of humanity, fairness, justice, and things of that nature; truth and honesty.

And you can probably break it down some other ways, but an idea I’d like to get across to everybody is that character is not just one little thing. It’s not just honesty or not just grit or self-regulation. There’s a couple of dozen, perhaps different aspects of, or things that can be thought of as character traits in people— positive character traits.

Denver: And psychologists, they’ve identified what they call the “big three factors” in shaping character. What would those be?

Mike: Well, so education is very important; leadership capabilities; experiences, which we try and do at West Point; and then skill-building curricula. So, a very important piece of trust, which we think is a critical component of leadership, is competence. So, you build skills; you build competence. As you build competence, you build confidence. And that interacts then with the ability to leverage positive character traits like honesty and integrity in that leadership context– to have a person who can be not just good at their job, but who can be trusted to lead you in the right way.

…you could be Number one in your class academically, but if you fail in character, you have failed in leadership.

Denver: Got it. Yes. Building leaders of character, Bob, became your passion while serving as the Superintendent. West Point has touted three basic goals for cadet development: academic, military, and physical fitness. Why did you believe it was so important to add character development as the fourth component?

Robert: Thanks a lot, Denver. Building leaders of character was right in our mission statement because we felt it was so important. We do have military development, academic development, and physical development. Our mission statement says that we educate, train, and inspire leaders of character. You’ll notice, though, it doesn’t say that you educate, train, and inspire leaders who are intellectually adept or physically adept. It says to educate, train, and inspire leaders of character. And the reason is simple: because you could be Number one in your class academically, but if you fail in character, you have failed in leadership.

The most important element in effective leadership is trust, and the best way to gain trust or to lose trust is to be a man and woman of character or have no character. So you can be Number one academically, and if you fail in character, you failed in leadership because you lost trust. As simple as that. So building leaders of character at West Point became the most important thing that we were doing.

Denver: And it was all codified in West Point’s Leader Development System. Tell us about that program and the five character attributes needed to be an effective leader.

Robert: The Leadership Development System was really designed on not only developing the values and attributes of effective leadership, but also to develop the person to be an effective member of a team; and to be able to lead teams and to build teams and to be a member of the teams, and also to learn how to be a follower within a team because you’re working for somebody else. But the attributes, the individual attributes of the leadership development were tremendously important, and the character aspects were a piece of that.

The character aspects were really defined by our values that we had at West Point: values of duty, and honor, and country. And the Army had its own set of values, which was loyalty, duty, respect, selfless service, honor, integrity, and personal courage. We pulled those values and those are the values that we taught. Those are the values that we wanted to be internalized through educational and experiential opportunities. And those are the ones that they were successful and, in some cases, they failed at. We didn’t look at failure as something that was permanent. We looked at failure as an opportunity to grow and to learn and to get stronger and to develop, and that– how we reacted when there was a failure was an important part of that leadership development program as well.

Denver: Such a healthy perspective. Mike, is there much or even any character education going on in our schools, and is there a desire for it?

Mike: I think there needs to be more, and I think there is growing awareness. And one thing that excites me about that is what we’ve done at West Point, where we have very systematically integrated character education into our general curriculum.

So, for example, every cadet takes General Psychology for Leaders their first year at West Point. And in that course, there’s explicit instruction of the psychology of character. They get to practice that as leaders and followers. And then in their junior year, they take a course called Military Leadership. The first two or three lessons completely devoted to the character, but it’s a course on leadership so that’s infused throughout that. In their senior year, they get another course, and along the way… I won’t take too much time. It can take us sort of a whole 35 minutes describing this. Many, many opportunities to practice in the field what they learned in the classroom.

Now, the reason I bring that up is I think it becomes what West Point does on our scale for 18- to 23- or 24-year-olds can be an inspirational model for what K-12 might do. So, for instance, there are two West Point graduates who have developed character education programs for K-12. One is a Lieutenant Colonel in the reserves. Now, Mike Erwin is doing this thing through something called “The Positivity Project,” and he’s got more customers than he can actually fulfill in terms of schools that are interested in character education.

Denver: There is the demand.

Mike: It’s big. Another one of our recent cadets who graduated, I believe in 2012 or so, I think Bob might remember the exact date. Danny Wang now lives in Hanoi and started up a very similar enterprise in Southeast Asia, with probably the same goals, to imbue the youth of Vietnam — and he’s now branched out even to Thailand and elsewhere in that region — explicit curricula designed to help teachers achieve that goal.

…emerging data from character science suggests that we can change our character in desirable ways throughout the lifespan.

Denver: After the formative years, Mike, is it possible to alter one’s character? Or is it pretty well set? In other words, is it too late for me?

Mike: Well, that’s something that pointy-headed scientists argue in very articulate ways. So I remember there being this discussion in the literature of psychology: If honesty is a trait, is it something that’s specific that an individual helped etch in stone by the time you’re 18 or 19? And then how much of it is situational? In other words, are you honest as a general characteristic across all situations, or is it brought out more or less so in different situations?

But I think the emerging data from character science suggests that we can change our character in desirable ways throughout the lifespan. Maybe Bob would comment on this as well, but I think sometimes it requires a triggering event. Sometimes those triggering events can be adverse things like the pandemic, or a cancer diagnosis, or something that really forces you to turn or look inward at your values and reassess who you are and the kind of person you want to be.

Robert: If I could jump in, Denver –

…when you are faced with some kind of confrontation, your action really is the manifestation of the character that you have, or the values that you’ve internalized…

Denver: Yes. Please do.

Robert: — like Mike has suggested. I think that when you are faced with some kind of confrontation, your action really is the manifestation of the character that you have or the values that you’ve internalized. Said another way, if I’m holding a cup of coffee that’s filled to the top and someone hits my arm, whether I want to or not, what’s inside that cup of coffee is going to spill out. So if I’m in a situation, and I’m confronted, and my reaction, my natural reaction is really the manifestation of those values I’ve internalized.

You may like those values, or you may not like those values, but those values really illustrate what your character is like. And if you do not like the values of how you react in that situation, then yes, I really believe you can change your character. You can study about it, and you can put yourself in experiential means. You can reflect and have introspection on what you really need to do and how do you need to modify that. So that when you’re confronted with that situation, then you have learned, and through that experiential event, you have become better and stronger as a result.

Denver: It’s really embedded in the DNA because there’s that reaction, without even thinking, is how you respond.

In the book, you talk about strength of the gut, the heart, and the head. I want to touch on each of those if we could, starting with the head. And Bob, this might be best illustrated through the story you tell of the dilapidated tomato paste factory in Iraq. Tell us that story and some of the takeaways from it.

Robert: So this was a situation in the city of Balad, which is right outside Samarra. Samarra was where you had the Shi’ite mosque in the middle of a Sunni city that was blown up by a guy named Zarqawi in order to really generate the Sunni-Shi’ite strike. I always say that because it was a very volatile area when we got there, and it was during the surge in that particular period.

So we had a commander who really analyzed the situation out there. This was an agricultural area, and they had not been farming since the beginning of the war, since the 2003 timeframe. They knew that they needed to start farming again. So this commander, without firing a shot, found two wealthy Iraqis, and he developed a relationship with them. He convinced them to pool their money together and to create a bank. Well, after Saddam Hussein, there was no such thing as a bank because of Saddam.

So what’s amazing is he had the skills to develop a trusted interpersonal relationship with these two Iraqis, and they trusted him enough to listen to him. So they pooled their money and they started loaning their money out. And there was this factory that used to make tomatoes or tomato paste that was all dilapidated. It wasn’t working anymore, and they needed a loan to get the repair so they can get this thing up and running again. So these two bankers went ahead and gave them a loan.

They got the tomato paste factory up and running again, and all of a sudden, there was a market now for the farmers to start growing tomatoes, which they hadn’t done for about four years, three- or four years. So the farmers wanted to start farming, but if you’re going to farm it in Iraq, you got to get the water out of the Tigris River into the canals, out of the canals into the fields, which means all those canals over three years of war were all dilapidated. They had to be repaired. So the farmers put pressure on the local government to repair the canals, to get the silt out of there, get them up and running again. And all of the pumps have to start working, which means you had to get the electrical grid up and running again. The farmers put the pressure on them to do that, and they reacted to it, and they did.

So all of a sudden they had all these tomatoes. There was all irrigation. The tomatoes were growing like crazy, and they’re bringing it to the tomato paste factor, clogging up the highway. And that created entrepreneurial will to plow out the field so that they can have a parking area. And then you had someone that built a couple of snack bars, and someone actually put up a small hotel. And all of a sudden the place started booming economically, and the place became one of the most peaceful areas.

It was a volatile area, and then it became one of the most peaceful areas because of the intellect of this man to understand the natural hierarchy, or where to put pressure, understanding the second- and third-order effects, and then to have the interpersonal skills to develop relationships without firing a shot. His effectiveness on the battlefield was not a weapon. His effectiveness was his intellect and the agility to be able to recognize opportunity.

Denver: Great story, and one of many you tell in this book, you guys. Second is the strength of the gut. And it’s interesting to read, Mike, that the only factor that reliably predicted which cadets would make it through basic training or not was grit. You have done so much work around grit, along with Angela Duckworth. Share with us some of what you’ve learned.

Mike: So an interesting question is: Are there particular outcomes or goals for which grit is more or less important? So what you described, West Point’s cadet basic training, in just an informal parlance, that’s really a gut check. It’s like basic military training anywhere with some added stuff thrown in.

So, in some ways, when a young person who’s used to sleeping in prior to coming to West Point, maybe 9 o’clock or 10 o’clock in the morning and just kind of living the life of a teenager or a young person, meets West Point for the first time, and all of a sudden is getting up at five in the morning. And maybe pretty soon we’ve got him out in the field, and they’re cold or they’re a little bit hungry, and they’re away from their social network of family and friends… that truly becomes a gut-check and doesn’t really have much to do with your IQ. So that stubborn streak that says, “By gosh, I’m going to get through this, no matter what!” That really defines what I think grit is mostly about.

One thing we’ve really found interesting about grit — I think this really gets to the heart of our notion of the character edge, as characters being an edge to a blade, which makes you even better — is that even for things for which SAT scores predict really well, like first-term freshmen, in our case, plebe academic performance, if you combine high SAT scores with high grit score, you get a marginal enhancement in the success of those young people. So in a sense, it provides that edge.

So we…Angela Duckworth and I and some others recently published an article that looked at 10 years of data among plebes. We looked at getting through their first summer. We basically replicated that and showed that to be a very valid phenomenon, finding what you just described, based on 11,000 cadets, not just 1,500. And then we looked at: How well did they do over the 47 months? How well did they do in academics? Largely more a head strength as well as a gut strength. How well did they do at military leadership, and how did they do at physical fitness?

And it turns out that over those three things over 47 months, grit plays a greater or lesser amount, depending on what you’re trying to predict. And then finally, we wanted to know at 47 months, so basically four years, who’s still there? Who is still there and graduates? And grit, over that entire 47 months, was important in hanging in and finishing what you start.

I think the moral of the story is twofold: One is that when you’re trying to predict human achievement and success, while grit is really, really important, other things are important, too; and how talent does matter, and strength of the heart matter, and strength of the head matter. And the second thing I’d leave you with from this, your question, is again, this notion that character in general, not just grit, provides that edge, especially among elite performers. You’ve got to be pretty good to get into West Point. You get 1,200 new kids that come every year. They’re all pretty good. What makes the difference in the long run? And we think that character is a very important piece of that.

Denver: You know, speaking about grit, I was thinking about an old BASF commercial. I don’t know if you remember them, the German chemical company. And they said, “We don’t make the carpets. We make the carpet stronger.” And it just seems like grit with all those other things, they make all those things better when you apply grit to all those other different areas of endeavor.

So, well, speaking of early mornings, Bob, I see that you’ve brought that spirit down to South Carolina with your 6 o’clock workout. So I’ve been following you on Twitter. I know what’s going on. But let’s talk about strengths of the heart, and that is brought home by your own story and that of First Lieutenant Daniel Hyde. Could you tell us about him?

Robert: Yes. Thanks. It’s a tough story, but thanks for the opportunity to tell it because he’s an incredible man. He was. So Dan Hyde… when I was assigned to West Point earlier as the Commandant of the Cadets, which is similar to the Dean of Student Affairs. I had done that, and I left, then went to combat with Dan Hyde. Had had another assignment; then I came back as a superintendent.

But I knew Dan Hyde back then as one of the senior leaders of the entire class. He had actually elevated himself as one of the top four or five students in the entire class. Tremendous talent, tremendous young man. So much potential– intellectually, physically, anything. Incredible man of character. And for whatever reason, he ended up in the 25th division. So that when I left West Point at that time, I went to command the 25th division. And shortly after I got there, the entire division deployed to Iraq. And he happened to be in Samarra. He was one of the ones in Samarra at the time.

So I was with General Odierno, who was the commander, and I got a message that one of our platoons down in Samarra was in a pretty tough firefight. I knew Dan Hyde was down there, and I had always… I was always kind of looking after Dan Hyde because I had such a close relationship with him. And so they were giving me notes and giving me updates on how the flight was going and stuff like that, and I didn’t know if it was Dan’s platoon or some of the other platoons. And then I got word, it was Dan’s platoon, and then I got word that he was killed. And I knew his mom and dad, and it was just tragic.

So it was one of those things that really hurts. It hurts you right in the heart. And so I went out, I flew down there and just spent some time alone with him afterwards. And you just tell them how sorry you are and how unfortunate. But one thing I always committed to Dan Hyde is that we will never forget Dan, and we will never forget his sacrifice. There is some incredible sacrifice that those men and women have given to our nation and to what our nation is today, and we must never forget their sacrifice and what they have done.

So Dan Hyde is very special. I still wear his bracelet so many years later. And the reason I do is because I never want to forget, and I never want to forget the sacrifice of those men and women and what they had done for their country.

Denver: And you’re still in touch with his parents.

Robert: I am. I do. I am. In fact, I just sent a note on Facebook to his mom the other day, just the other day.

Denver: It’s a tough story, and thank you so much for sharing it. I want to go back to this, Mike, if I can — trust. There’s a chapter in the book, “Trust the straw that stirs the drink,” and ain’t that the case! Through your research, what are the factors that go into building trust? A lot of people don’t know how to do that.

Mike: So let’s give credit to a colleague of ours from West Point who’s now retired, Patrick Sweeney. Dr. Pat Sweeney, retired Colonel. Pat’s down at Wake Forest University now, in their business school.

When Pat was a graduate student, Dave Petraeus, then Major General Petraeus called and said, “You’ve got to get out of graduate school and come and help us. We’re going to war.” So back in March of… the events leading up to the March of 2003 in Iraq. So what Pat had the sense to do and the presence of mind to do is to say, “Hey, I’m going to go… I’m in my doctoral program. I’m going to collect data in the field, like while we’re actually in combat, on trust.”

So what I’m going to say about this really comes…I want to give credit to Pat Sweeney and his insightful work on it. Because academics tend to look at trust and a lot of these things in very artificial conditions. They may give surveys to freshmen, or they may survey some arcane sample of workers, and it’s just not the same as studying trust in a situation where life or death could occur.

And so, what Pat has found is that, and we believe, Bob and I believe, this is characteristic of lots of occupations, many of which are, of course, tip of the spear things like law enforcement and fire departments, such as that. But there are three components to trust and they are: competence — and we call them the three Cs.

So if you want to be trusted as a platoon leader or you want to be trusted as a shift Sergeant in the police department… or you name the field… better know the job really well on all the details. So I wouldn’t really expect that platoon leader to ever probably break out the machine gun in a battle and lead the charge. That’s not really there. But they better know what they’re doing so they can demonstrate to the soldiers this degree of competence. And the more you do that, that’s a really good point towards building trust.

Denver: You have to know how the business works, whatever the field might be.

Mike: Absolutely.

And the second then is character. And as Bob said before, you can be the most competent cadet, but if you fail on character, you fail on leadership. So building character… I would almost argue that the first thing you should do is to assess your own character. We talked about that in Chapter 1 of the book, and there’s a very nice online survey, which gives really good results, and it’s in the book. And so you figure out and become aware of what your 24 character strengths are. I believe there’s 24. Scientists believe there’s 24. Look at the rank order. What’s your top five or six? What’s your bottom five or six? And as you build self-awareness, that then allows you to have insight into how to leverage your strengths — now, your character strengths — to accomplish difficult goals and to lead others.

So I think the thing about character, if you look at it as a 24-dimension thing as opposed to one dimension thing, is: we all have strengths and we all have weaknesses. So my strengths, being a professor and all, all traits of the head more so. I’m pretty good at self-regulation, and I’m very, for some reason, high on forgiveness. But otherwise, I’m not so strong in some of those other categories. And you, Denver, if you take this thing, you’ll find your own distribution of strengths.

Again, the beauty of the strength model is there are different ways to leverage your own strengths to achieve almost any different goal. So you’ll find two equally trusted leaders who may employ, sort of tend to employ different character strengths in order to achieve that goal. So I’m actually saying awareness is a really important piece of becoming a competent and high-character trusted leader.

And then nurturing, the third C is caring. True, genuine caring for those who serve with you and under you, so to speak. And that is something that, once you’re aware of it, there are certain behaviors you can practice, even — it may sound a little artificial, but practice remembering the birthdays. Practice stopping to take time each day and talk to people and ask them how they’re doing. So there are some things you can do along those lines. And if you could do all those things together, then I think you’re building trust.

Denver: And I should point out to listeners, there are some character building exercises in the book to follow, and they’re really, really very interesting.

So, Bob, you recently became president of the University of South Carolina, as I mentioned in the opening. And that can be a difficult transition, especially for someone coming, let’s say, not out of the traditional world of Higher Ed, but it’s gone very, very well. What have you done and some of the things that you’ve endeavored to do to earn the trust of that community? What does a new leader need to do in a community to earn trust?

Robert: Well, thanks, Denver. You’re absolutely correct. So as an outsider to the traditionalists, for presidents of higher education, although coming as a president of West Point, and not coming up in the career path in that particular manner, that did raise some skepticism, and I recognize all of that. So I do recognize that this was an issue of trust, and it’s trust that has to be earned. Trust doesn’t happen automatically. You really have to earn it. And the first thing that I did is to try to build as many bridges, interpersonal relations, engage with people, knockdown whatever walls were out there, and listen. And listen.

And so the first group I met with were students that were concerned about me coming there. So I met with them right upfront. And then I met with faculty members. I met with all the trustees one-on-one. There were some trustees that were in favor of me coming and some not. And it was just an issue of building relationships and building trust as a result of that.

And then there were other constituents that are out there as well. We’re the flagship university, one block away from the statehouse, which means we have legislative issues and political issues all the time. So I really realized how important it was to develop relationships with the legislators. And then we had to develop relationships since we’re an urban campus right smack in the middle of the city of Columbia, where 80% of our students live off-campus in the community; that we had to really develop relationships with those neighborhoods because students like to have social gatherings at all hours of the day and night, as you can imagine. So–

Denver: Yes. I can remember.

Robert: And so it’s important to build those relationships, but trust is the heart of it all, and that is to build that trust relationship.

Furthermore, as a public actor — this is a public institution, and even those in the military are also in a public institution, the United States profession of arms — that our client in this endeavor is those whom we serve. It’s the people of South Carolina in my capacity as a flagship. And in the United States Military Academy and the United States Military, it’s the people of the United States of America. And if in this profession, whether it’s the profession of arms or of higher education, your clients are those people, and as a public actor, as a public servant, you have to develop a relationship with them. And that relationship has got to be strong, and it’s got to be built on something, the best way to get a strong relationship is to build it on trust.

And trust, like Mike said, is a function of not only your competence but is also of your character and also of caring. And when you demonstrate caring, and character, and competence to those constituents out there, the natural thing that will emerge out of that is trust. And once you have trust established, you can lose it. But once you have trust established, it’s important to nurture it and to maintain it and to continue it to grow, because otherwise, they’ll naturally atrophy.

Denver: And Bob, so far, we’ve been talking about individuals, but there are also high-character organizations. I know one would be Johnson & Johnson, led by a West Point alum, of course, who lives by a credo every single day. Tell us about that, Bob, and the hallmarks of a high-character organization.

Robert: It was really a pleasure to interview the president of Johnson & Johnson, and to hear him talk about the creed. And frankly, that creed was put in place when Johnson & Johnson was established way back in the early 1900s, and they kept it. Alex Gorsky is the president and CEO, and Alex actually understands the creed, not only as a set of values to aspire to, but also to develop the current leaders and the future leaders of the institution. That’s an important point.

The point is that you just can’t assume people are just going to embrace the values. It’s a developmental process. And so, he has regular sessions, and he sits down and talks to his first, the first reports that report to him. And he evaluates them on the creed and the values within the creed. And then he says, he sits down and talks to them on a regular basis on what’s strong and what’s not, not only as an individual but the role the individual plays for the institution.

And you remember way back, I think it was in the 1980s or ’90s when they had the Tylenol incident.

Denver: Oh, yes. Yes.

Robert: But it was really interesting to see how Johnson & Johnson had reacted to that in transparency in order to regain the trust of the public, the constituents of that, because they could have easily lost all trust. And then the whole place would have fallen in. But it’s really a great lesson and see how they had to, through transparency and communication, demonstrate their competence, how they’re handling this, and then what they needed to do to regain the trust of their constituents. And they did.

Denver: And picking up on that, Mike, you draw a distinction in the book about losing trust between the Catholic Church and how they’ve responded, and GoFundMe and how they responded. Tell us what that story is.

Mike: I think in almost every case when you look at organizations that do well in the face of a crisis, versus those who don’t do so well, if you just look at it from the lens of competence, character, and caring, you can differentiate between those two.

And so, the GoFundMe site, this is just a quick summary of this. There was a husband and wife who conspired with a veteran to defraud them. So you get people to give money to GoFundMe, and they walked away with a lot of money, bought a shiny car.

Denver: Tons of media coverage that story had.

Mike: Yes. It was all over the place. Yes. And so, rather than deny it or avoid it, or stick their heads in the sand, what the GoFundMe people did is they said, “Look. We know how to fix this. We’re going to take future actions.” They demonstrated competence, “Here’s a plan that’s going to address this to keep this from happening again. We implement new security checks into the system,” and so forth establishing competence. They showed character by not, frankly, lying about or denying it. And they showed caring by the fact that their whole set up is to help others, those who are in need; the whole company’s about caring. So they have all these three Cs in place.

Now, the Catholic Church has a lot going for it, but a couple thousand years of history of doing great. And so, they hit this rough patch with — and I don’t want to diminish that because there’s evidence to suggest — that in the American population, at least based on opinion polls, confidence in the Catholic Church has been eroding and at the same time, these sex abuse scandals broke.

But you could easily walk away with the impression through the years that the church would deny this happening on a large scale, and it was just a bad actor, a bad person who picked their parish. Then you read about people who’ve been accused, priests who’ve been accused of this being just given another job someplace, and no real consequence.

And so, Catholics and others who are looking at them may begin to question the competence of the church in their approach to dealing with the problem… their character and being honest about it. If you really cared about your parishioners and the church, wouldn’t you try to fix that pretty major problem?

Denver: Absolutely.

Mike: The good news is: religion plays such an important role in people’s lives, and it’s a character boosting thing. They’ve got a good basis to rebound from by reestablishing competence and how they go about dealing with this, demonstrating character now– positive character, in dealing with the situation… and then as much caring as they can heap upon those would be quite helpful.

Denver: And have you seen instances, Bob, when a leader’s failure of character has not only affected him or her, but the entire organization and its ability to complete the task it’s been assigned to do?

Robert: Absolutely. I see it all the time. And that’s one of the consequences of failure in character because it not only affects the individual, but it affects the entire organization.

So in the preface of the book, I tell the story of one of my battalions up in Mosul, one of the hottest places in all of Iraq, and they lost their commander who was a beloved man of great competence and character. And it really had an impact on the leaders and then throughout the entire battalion. We quickly got another commander and put him in there, a very competent commander. But he had some other character issues. And as a result, we had to remove him.

So, within a period of just a couple of months, they had gone through two commanders: One who was a man of great integrity and character and competence, and one who was not. And the competence of the unit, particularly in combat, was hugely affected. And so, I had some great concerns, and there had to be some retraining that was going on among leaders and among smaller organizations within the big organization. If I had the ability to pull the entire battalion out of combat and then retrain them with leadership and then put them back in, again, I would have. You just physically can’t do that.

But character… you’re exactly right. It does not just affect the individual and the consequences to him or her, it affects the entire organization that they’re in charge of.

Denver: And then even after you replaced that person, that damage can still linger as the next person comes in. It just doesn’t magically go away, does it?

Robert: No, it doesn’t. With a person with great character, they can really turn the thing around, and they can do so quickly, but they always have that other thing that’s lingering around from before..

Denver: Finally, gentlemen, I don’t believe anybody would dispute, at least anyone who has a TV, that there is a crisis of character in this country. There’s a breakdown of trust in virtually all our institutions. And I think now, we are not even beginning to trust our fellow citizens. Maybe you could each say a final word about that, the contribution you hope this book will make in bringing character-driven leadership to the public at large, and what winning the right way means. Let me start with you, Mike.

Mike: That’s a good question. And one point I’d like to get across is that I’ve been studying as a scientist, I’ve been looking at character almost 40 years. And when I first started looking at it, I looked at character as something that was pretty much something inside of you — you as an individual are honest, or you have self-regulation, or you have grit, or you have kindness, or whatever it may be. And the more and more and more that I study it, and the more I’ve worked with people like Bob Caslen who’ve lived that life of leadership in demanding situations, the more I’m coming to understand that character, that the organization itself may be more important than what’s inside of you in bringing out the good or the bad in a person.

So when I see the situation today and every day, you open up all of your preferred news media sources, and there’s a crisis of the day, and this politician said that or that politician said something else, and you don’t know what to believe, and it does erode trust because it’s violating that competence… and we should all be evaluating for people we’re going to vote for— competence, character, and caring.

Now, we all have different lenses, right? So I resist the temptation to point a finger at a given individual and say, “Well, it’s so-and-so’s fault as a leader. This is his problem.” At the end of the day in a democracy, it’s we, the people who elect our leaders. So I think that’s just my one reaction — I kind of leave it at that. You probably want to hear about what Bob’s got to say — is we have to look ourselves in the face about who we choose to lead us at the national level and the local level. So I think we need to share the blame, if blame is to be assessed, and in successful cases, share the success stories as well when we get good people in. Does that make sense to you?

Denver: It does. I think there’s far too few mirrors around and far too many fingers pointing. No question about it. And that’s exactly where we’re at. And I had a behavioral scientist on the show the other day talking about decision-making, talking about the person and the individual. He said the breakdown is the opposite of what we would think. It’s 30% on the individual and 70% on the environment that they’re in. And that is just the opposite of what most people think. So, the culture and the organization and the environment, to your point, Mike, plays a profound role.

Mike: Yes. If you see an organization that wins consistently, like I’ve done some work, just informal consulting with the San Antonio Spurs– they’ve been good for a quarter-century. That’s not happenstance. They have a very healthy, robust, positive culture. On the other hand, you fill in the blank NBA fans, another team that consistently fails year in, year out, probably something going on at the organizational level. And so, I always am coming more and more just to look at the organization first and foremost, maybe 70% of the time, and then put that other 30% on the individual.

Denver: I think you’re absolutely right. And Bob, your thoughts?

Robert: Well, first, I would say that you’re right. Whenever you point your finger at somebody, there are three fingers pointing back at you. Our country has seen worse times and worse divides, and they’ve come through it. So, I feel confident that our country will again. That means to say that we are in the middle of a divide right now.

I think there are a couple of contributing factors to this. I think…Thank God for the increase in technology, but social media has really kind of put a whole different dimension on that, and it’s like… Marty Dempsey wrote a book and in Chapter 1, he called it the digital echo, that you can say something on social media, and it can go viral. And it doesn’t matter if it’s true or not. What matters is how many likes you get. So the whole essence of what is important now is not necessarily facts and truth, but likes, and it kind of distorts reality out there.

Denver: Great point.

Robert: So I think that we, at some particular point, have got to take a look at social media and how to get that back into the box from a character perspective because it destroys trust. That’s what happens.

So if we’re in this divide right now, and I just think of the divide as I look at all different aspects of it, it’s just selfish. We’re looking at ourselves. I’d love to see a leader who is not necessarily humble, but is selfless… that looks at selfless service, that wants to serve the people of the country, that wants to serve the people of their state and wherever they’re being, running for office from. And selfless service is one of the values of our army, and it’s one of the values that we talk about from a character perspective as well.

A good example of a very divided nation and having a leader come together to unify it was Nelson Mandela, of all people in South Africa. It’s a great story in itself. So, Nelson Mandela is thrown in prison for X amount of years, I forget.

…the forgiveness that he demonstrated was powerful. It created empathy. And when you create empathy, you find common ground. And when you can find common ground, then rather than point fingers at each other, you find common ground that you can latch onto together, and then you can move forward together.

Denver: Twenty-seven, I think it was.

Robert: Yes. So, what does he do when he comes out of prison? Rather than being resentful, he forgives those who put him in prison. And the forgiveness that he demonstrated was powerful. It created empathy. And when you create empathy, you find common ground. And when you can find common ground, then rather than point fingers at each other, you find common ground that you can latch onto together, and then you can move forward together.

But it really started with a leader who demonstrated humility and forgiveness, and by demonstrating humility and forgiveness, two very powerful values; and then that brought the country together so that they can move forward. And he ended up being a powerful leader and a very effective leader in unifying that nation. We need to find a Nelson Mandela here in the United States for sure.

Denver: That’s for sure. That’s for sure. Well, as they say, radical change, one of the keys to it is to forgive your enemies because you’re going to need them. There’s no question about it.

Denver: That’s for sure. That’s for sure. Well, as they say, radical change, one of the keys to it is to forgive your enemies because you’re going to need them. There’s no question about it.

The book again is The Character Edge: Leading and Winning with Integrity. If we can address this issue, it will allow us to successfully tackle so many of our other challenges. And you’ll find this book to be the perfect field guide for that. I can’t thank you both enough for being here. It was a real delight to have you on the program.

Robert: Thank you very much, Denver. We enjoyed it very much. Thank you.

Mike: Yes, thank you, sir.

Listen to more The Business of Giving episodes for free here. Subscribe to our podcast channel on Spotify to get notified of new episodes. You can also follow us on Twitter, Instagram, and on Facebook.