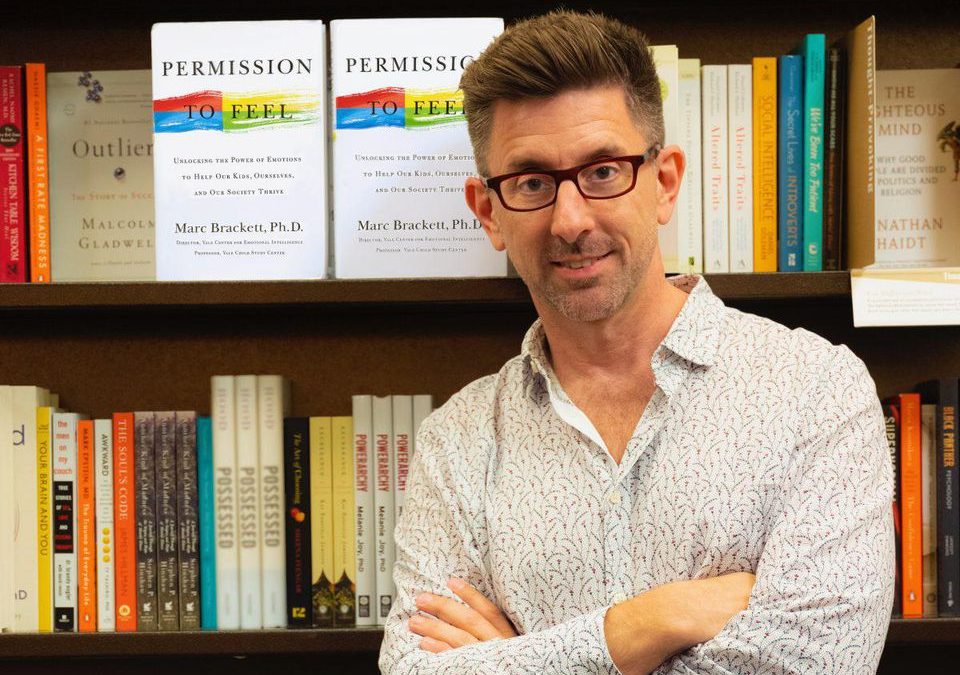

The following is a conversation between Mark Brackett, Author of Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help our Kids, Ourselves, and our Society Thrive, and Denver Frederick, the Host of The Business of Giving.

Dr. Marc Brackett, Founding Director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and Author of Permission to Feel

Denver: With the pressures, stresses, and uncertainties of the current moment, emotional intelligence has never been more important. And it’s a pleasure to have with us today the foremost expert in the field. He is Dr. Marc Brackett, the Founding Director of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence and Author of Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help our Kids, Ourselves, and our Society Thrive.

Welcome to The Business of Giving, Marc!

Marc: Thank you, Denver. I’m excited to be here with you.

We see emotional intelligence as a skill, as a mental ability that simply has to do with how we reason with and about our emotions.

Denver: The term emotional intelligence gets thrown around pretty freely, and often with no degree of precision. How do you define emotional intelligence or EQ?

Marc: We at the Center ascribe to what we call “the ability model,” that we see emotional intelligence as a skill, as a mental ability that simply has to do with how we reason with and about our emotions. That’s the broad definition.

So think about that “reasoning with and about your emotions.” So it’s complex problem solving that involves reading emotion — so I’m looking at you over the Zoom meeting and trying to figure out how you’re feeling. I’m also trying to figure out “What am I feeling right now?” That’s the recognition. We call it “RULER of emotion,” the recognition. The “U” is understanding emotion — so, where is it coming from? What’s the cause of the feeling? The “L” is labeling — having the language to describe those feelings. The “E” is expressing emotions — knowing how, and when to express emotions. And the “R” is the regulation of emotion.

Denver: It really sounds it’s important to stay present in the moment and have a moment of self-observation, which I think a lot of people don’t do. But to take that moment and think about what’s going on is a lot, at least, of what I think you said. And I think of the five things you just mentioned there in the RULER, the one that people are always most concerned about is regulating emotion. What are some of the best strategies for doing that?

Marc: Oh, my goodness. That’s a big question. That’s like three hours.

Honestly, I always start off with the principles in my book, which is that to me, the very first step in regulating is giving yourself the permission to feel because regulating is misperceived a lot. I was on a call last night actually with a group, and a guy was like, “I don’t want to regulate my feelings.” And then I said, “Well, do you have children? He’s like, “Yeah.” I said, “Have you ever gotten really irritated with your kid?” He’s like, “Yeah.” I said, “Did you ever feel like you needed to get that anger down a little bit so that you could have a good conversation?” He’s like, “Yeah.” I’m like, “Well, that’s regulation. So you’re doing it. You just don’t like the term because it sounds like it’s controlling or something of your emotions.”And so, for me, emotion regulation starts with giving yourself the permission to feel that it’s okay to be anxious right now. It’s justifiable to be angry right now. It’s okay to be happy and content. There’s no bad or good emotion. That’s the first step.

The second step depends on… it’s really about goals and strategies. So, do I want to keep this feeling, or do I want to shift this feeling? Am I highly activated? For example, if I’m really overwhelmed, my brain operates in a different way than when I’m calm. So if I’m freaked out, I need some physiological strategies. I need to help myself down-regulate so that I can think clearly and be present so I can problem-solve. So permission to feel physiological deactivation — breathing exercises, mindfulness, taking a walk, pausing. And then comes all the rest of the stuff, things like positive self-talk versus negative self-talk; engaging and reframing as opposed to blaming; relationships, keeping good routines, healthy eating, exercise, sleep. It’s all interconnected.

Denver: And a big piece of this, too, is labeling and having the right vocabulary to describe what that emotion is. You’ve done some work in this area where you’ve co-developed something called the Mood Meter. Tell us how that works.

Marc: The Mood Meter is our tool. I can even show it to you because I’m never without my mood meter. Actually, it’s in my stuff, on my little poster there. This is the mood meter on the inside of my book.

The Mood Meter is a tool that’s built in a tremendous amount of science that says that how we feel is a product of two basic dimensions of human functioning. The first is our appraisal of the world around us and our internal world: Do I feel pleasant? Do I feel unpleasant? Do I feel like approaching? Do I feel like avoiding? Do I feel comfortable? Do I feel uncomfortable?

And so, think about that in terms of survival. It’s like “I’m looking around. OK. It’s safe. I can enter. Oh, no, it’s not safe.” Then the Y-axis is energy, technically called “activation” or arousal, and that’s really checking in with your: Do I feel like I could thrive? Do I feel like I’m energized? Do I have the strength to fight away the enemy? Or am I depleted in my resources and just feel exhausted and tired?

And so those two things cross — pleasantness and energy — to create the four quadrants: yellow, red, blue, and green.

Yellow – high energy and pleasant, excited, happy, elated, ecstatic, optimistic, hopeful. The green – pleasant but lower in energy, calm, content, tranquil, peaceful, relaxed. The blue and the red are unpleasant — and again, mindset here — unpleasant, not bad. I’m going to say that again. They’re unpleasant, but they’re not bad. The blue – down disappointed, sad, lonely, hopeless, despair. The red – angry, anxious, overwhelmed, scared, things of that sort.

Denver: It is important, it sounds, to accept every part of us and not to judge parts of us as good and bad; they’re parts of us; and to recognize that. In addition to the vocabulary that you just defined there, another way to identify our emotions and better understand them is to understand our personal history. What’s the link there?

Marc: What’s interesting about our emotions is that they’re created within us through our life experiences. And so, this is why what makes me angry may not make you angry. What makes me fearful may not make you fearful. There are global themes around our emotions, like fear tends to be based in danger, anger, and injustice, but our appraisals of the world around us differ because of our life experiences.

So I just think that’s so important, as an educator or as a boss or as a partner, is that you know we’re very egocentric in our world — whatever I feel and the reason why I feel is the reason why you should feel it. And that’s where a lot of errors come in; a lot of judgment comes in; a lot of misperceptions come in, and a lot of misunderstandings come in.

Denver: My sense of reality is reality, just not my reality. We think it should be everybody’s reality, and we operate from there. And that’s not a healthy way to go.

Well, looking at the largest landscape of this pandemic. Boy, tremendous stressors on society with COVID-19, racial injustice, economic insecurity. Is that changing the emotional landscape of our society right now?

Marc: Definitely. Because it’s not just a one-week thing, it’s not a one-month thing. This is now a half-a-year for many of us, if not longer. It’s changed the way education operates. It’s changed the way children interact with each other.

An example of that is my friend’s son who is in third grade, they’re doing remote learning. He’s been alone in his house with his mom. She’s a single mom. She works all day, and he’s doing his — whatever he’s doing all day, which is really hard for someone who’s 10-years-old to just be learning all day. I think they have an hour in the morning with their teacher, and then they’re supposed to just work on their own for three hours or something like that, which is unrealistic.

And then, so she was like, “My god. I feel terrible. He’s been all alone, just like locked in the room doing work all day. He’s struggling.” And so, they went for a walk at the end of the day, and she said, “You know, honey, maybe we should do some virtual… maybe we should get together for a social distance meeting with your friends.” And he’s like, “No, I don’t really think I want to… I need to see my friends any more.” And she was like, “uh-oh,” like “Houston, there’s a problem.”

And so we need to be really mindful of this pandemic is shaping many children’s development. For me at 51, I’m actually fine working from home. I don’t have to travel. I did this podcast with you without having to go anywhere to do it. I think it’s a blessing, like my life has gotten actually somewhat better from this terrible pandemic in terms of my wear and tear on my body.

Denver: I know what you’re talking about.

Marc: But I’m in a very different position.

And so, for a lot of kids and for a lot of adults…a father came up to me in a presentation — a virtual presentation, of course — and he said, “Marc, I’m a father, I’m a lawyer, I’m a caretaker, I’m a lunch manager, I’m a tech coordinator,” and then he just sort of almost cried, and he’s like, “And I can’t take any of it. ” And so, the reason why I share that is because I think that these multiple pandemics have woken people up about why emotions matter.

Denver: Once we get past it, and I know it’s hard for you to have a crystal ball, but do you think the way we live and interact is going to change, moving forward past the pandemic?

Marc: I think so. Somebody the other day said to me, “Do you think we’ll ever shake hands again? Do you think we’ll ever hug again?” And I think probably we will, but maybe not as much as we used to. Like, am I motivated to shake people’s hands? Not really. I can turn into a Buddhist monk in a matter of a blink of an eye and just… I don’t mind that. It’s like, “You know what? I send peace to you; you send peace to me; just don’t touch me.” But the distinction…

Denver: You kind of wonder what’s going to happen to dating and things like that.

Marc: I think luckily, and not luckily, people have strong hormones. So people are going to want to be with… people are biologically programmed to want to connect, but I think it’s going to be different, and we’re going to have to be really careful.

The vision that we have at our center is to make social and emotional learning integrated into what I like to say “the immune system of the school,” that it’s about how leaders lead, how teachers teach, how students learn, and how families parent.

Denver: Even looking at normal times, where is social, emotional learning in the schools as part of the curriculum? Is it happening or is it still more or less an add-on?

Marc: It’s both. The vision that we have at our center is to make social and emotional learning integrated into what I like to say “the immune system of the school,” that it’s about how leaders lead, how teachers teach, how students learn, and how families parent.

The problem is that we don’t have a national, a federal education department that really cares about this stuff, and so the messaging is mixed. There are psychologists and parents and teachers and school leaders who are saying, “We really need these skills, and they’re so critically important.” The business world is saying, “We want to hire people that have these skills.” So the desire is there for people to develop these skills, but the time to do it is not there.

Denver: Finding bandwidth… always an issue.

Marc: It is, but I think it’s time to reevaluate what education means. Think about remote learning, how much time is being wasted, and how much time can be spent thinking about the development of these social and emotional skills that are going to be critical to children’s success.

What’s very interesting…about the work on emotional intelligence that is different from other forms of education is that with math, there’s a correct answer… and that’s not going to change. But how I regulate depends on my personality…it depends on my mood. It depends on the context. It depends on who I’m with. It depends on the feeling itself. And importantly, there’s no correct strategy.

Denver: We’re never been very good at that as a society. We deal with the problems as an aftermath and not some of the measures up-front, which would avoid the problems in the first place, which saves a lot of time in the long run. I don’t know if you can describe this, but I’m going to ask you anyway, what would an emotionally intelligent classroom look like?

Marc: That’s a great question. It wouldn’t look like kids sitting in a row staring at necks. I can tell you what it wouldn’t look like. It wouldn’t look like the teacher being the sage on the stage talking at students for six hours. We know that’s what it would not look like. So I think to think about that question, you have to think about the skills that we want to develop.

So recognizing emotions. Think about that. Are we having opportunities to interact face-to-face, listening to people’s vocal tones? Are we sitting in circles so that we can see people’s responses to different things and how they react to different events? So we can start learning this skill.

Understanding the emotion. Do we know each other well? Do we understand what makes each person in our classroom feel a certain way and why they have those feelings? Do we have the common language to describe those feelings? Do we give every child the permission to express their feelings, and they feel safe and comfortable, no matter what they’re feeling, to share it with no repercussion? Are we giving kids opportunities to learn how to regulate emotions through cooperative learning, through project-based learning exercises? Are the teachers helping kids become emotion scientists themselves in terms of that self-exploration, and trying a strategy and refining a strategy?

So to me, it’s so clear, but I live this stuff. I think what’s very interesting, Denver, about the work on emotional intelligence that is different from other forms of education is that with math, there’s a correct answer, right? There’s like, yes, four plus four equals eight; eight times four equals 32; 10 divided by five equals two. And that’s not going to change. But how I regulate depends on my personality. It depends on my mood. It depends on the context. It depends on who I’m with. It depends on the feeling itself. And importantly, there’s no correct strategy.

So that’s hard for a lot of educators to reckon with because it’s like you want to give the kid a grade; you want to evaluate something, and the only way to evaluate emotion management, for example, is on really getting to know the child to see “Is this strategy for anxiety or anger or fear working for that child? Is it helping them achieve wellbeing? Is it helping them build and maintain good relationships? Is it helping them achieve their goals?” And so, it’s a little bit more open-ended and I think that a lot of us are uncomfortable with that form of education.

Denver: It’s also the complexity of the world these days, and we’re finding out that it’s really not that single answer, and often, it’s more, the questions you’re asking as opposed to the answers you’re giving.

But let me just ask something about that, somewhat related, which may be somewhat inconsistent with what you just said. Are we trying to measure emotional intelligence? Are there any efforts along those lines to get better at measuring it?

Marc: There are. So actually, our team is working on those assessments right now. We spent many, many years and have gotten significant amounts of funding to build these assessment tools. But again, these are not assessments to wean people out, or to preclude people from doing certain things. They’re formative in assessments to help people understand who they are.

And so, for example, the one we’re working on in regard to emotion and perception, we spent years videotaping different people across race and religions and backgrounds to make sure that it’s culturally responsive and adaptive. And it’s great to get feedback that “maybe you’re biased in the way you’re reading certain people’s expressions, or maybe you’re missing the clues in people’s facial expressions. “And so we find that people really want these tools. They actually want to know. They want to get the feedback. At least some people do.

Denver: Moving on from school, what can parents do to help boost their child’s EQ?

Marc: I think the first thing is they can be their child’s first teacher in what it means to be an emotionally intelligent person. So, I ask every parent: Are you the role model? What are the messages that you are sending to your child around healthy emotion regulation?

Like my mom who… my parents loved me, but my mom was like “I’m having a breakdown. I’m having a breakdown!” every other day. So I was like, “Oh gosh. I’m not going to talk to Mommy about my feelings.” My father was a tough guy from New York who just kept on, “Son, you got to toughen up. Toughen up, son!” And so, I learned like — “OK. Well, I’m not a tough guy. I don’t know what to do with the whole breakdown thing, so I’m just going to stay to myself.” I had a tough childhood. So parents, I think they just have to recognize that their kids are listening to them. Their kids are watching them and make every effort to be authentic.

So a lot of parents say, “Well, can I tell my kid I’m anxious? I’m like, “They’re going to know anyway, so you might as well be honest,” but make sure that when you share it with them, you don’t share it in a way that makes them feel like they need to take care of you. That’s not the job of a kid. The kid can see that. You can say, “Daddy’s had a really hard day at work. He’s really angry at one of his colleagues because this happened, and it was very unfair. I’m very upset about the way this person treated me, and I’m thinking about how I can respond to that. I’ve got to take my breath to calm down. I would have to come up with a plan about how I’m going to talk to that person tomorrow.” That would be amazing if families did that.

Denver: Another effort you’re involved in, Marc — and you’re involved in a lot of them — is a free emotional learning course for all school staff in Connecticut. That is incredible and very, very cool. Tell us more about it.

Marc: Honestly, this is one of the most exciting things that has happened in my professional life. A couple of years ago, the Dalio family, Barbara Dalio, who is a funder of our center and of many things in the state of Connecticut, we had lunch and she jokingly said to me, “Marc, what is your vision?” And I said, “I want to make Connecticut the first emotionally intelligent state.” She didn’t say anything. And then I got a phone call a couple of days later; she’s like, “Well, let’s do it.” And I was like, “OK. I don’t know how to do it. I just want it.”

Denver: That’s where it starts, though.

Marc: Exactly. You got to have the vision. Long story short is that the RULER, which is our approach to social and emotional intelligence … it’s in 3,000 schools across the nation, about 250 here in Connecticut, is slowly being integrated and adopted, but it’s a whole school commitment. After COVID hit and the murders of way too many Black individuals over the last couple of months … a couple of hundred years … schools and teachers are just freaking out about their own anxiety, about the inequities that they notice in their classrooms, in their schools, and communities.

And so, by some wave of a magic wand, everybody got on the bus. The Governor of Connecticut, Ned Lamont; the Commissioner of Education, Miguel Cardona; the head of the Superintendents Association, the head of the two unions, the CEA, the AFT, the head of this principal’s union, the head of the school board association, the head of this union… literally everybody was like, “We got to do this.”

And so I was blessed that they approached our center and they said, “Well, what can we do?” I’m like, “Let’s build a course for everybody.” And so, we’re in the midst of building that right now. It’s a 10-hour course called Social and Emotional Learning During Uncertain and Stressful Times. It really is about helping educators understand the psychology and the biology of stress, as well as evidence-based strategies to help themselves deal with their feelings, but also be supportive to kids. Right now, we have 17,000 people already registered, which is pretty incredible. And my hope is that Connecticut can be a model for the rest of the United States.

Denver: Scaling this is exactly the thing to do and exactly what we need.

Marc: We need to be responsive to what people need. It’s not about us. It’s about what the world is telling us they need, and our educators are struggling, and they’re responsible for the healthy development of, in Connecticut, 600,000-, 700,000 children. So in many ways, I feel like it’s our moral obligation to do this work because without it, we’re going to have a stressed-out classroom, a stressed-out school, a stressed-out community, a stressed- out state.

Denver: From my conversations, it was a tough first week or two of school for both the kids and the parents, and you can throw the teachers and administrators in there as well. It was really challenging.

Finally, let’s turn our attention to work. I know that you have co-founded a business. I think it’s called Oji Life Lab.

Marc: You got it. Great.

Denver: All right. And you’re trying to bring emotional intelligence skills to the workplace. How is the lack of emotional intelligence adversely impacting businesses and organizations?

Marc: In ways that every CEO should be worrying about. As I always say, emotions matter for everything. They matter for where people spend their time. They matter for the decisions that people make. They matter for the quality of relationships. They matter for physical and mental health, and they matter for activity and just everyday performance. And so as a manager or a leader, you’ve got to know that because how people feel in your organization is going to determine the quality of their work.

And we’ve done that. We’ve seen in our research that when there is an emotionally intelligent leader, there are people who are more inspired. There are people who feel less frustrated. They are less burnt out. They have greater job satisfaction. And the list goes on in terms of the differences. And so, they’re less likely to want to leave their job, so there are fewer turnover intentions. And when you think about the costs to our companies in terms of turnover intentions, you’d want to make sure that you train all of your leaders in emotional intelligence.

Denver: You certainly don’t want to have 70% of your employees disengaged as surveys indicate, and that’s a big, big piece of it.

So, I’m sure you’ve encountered this, but let’s say you’re running into a corporate client, and you’re meeting a lot of resistance– leaders who look at emotions as being weak, or maybe just look at this as all a lot of nonsense. What are you doing to break through?

Marc: I beat them up. No, I’m kidding. That’s why I got a fifth-degree black belt in the martial arts because no one’s getting in my way.

More seriously, I really go back to what I just said. I go to the science. A lot of business people, they’re not like they don’t want to hear the anecdotes. They want to see the hard data.

And so, I just think that’s why we have to do really good research to show, like I said a minute ago, how people feel is driving the productivity and their performance. And when you have data to show… when you know that inspiration is so important in an organization, and then you can show in an organization that management teams that have leaders with high emotional intelligence are performing better, have people who are more inspired and engaged, versus the groups that have supervisors who are low in emotional intelligence, it’s very eye-opening. It’s almost like I couldn’t even think about it. How could a leader dismiss this work when there’s hard data to show that the groups with leaders with higher emotional intelligence are outperforming, have better physical and mental health, less burnout?

Denver: Very smart. You tie it to outcomes and that pretty much…. that’s the story. Generally speaking, are we getting better with the skills of emotional intelligence? Or could it be that we are actually getting worse?

Marc: I don’t know the real answer to that because we haven’t really had the assessment tools or the longitudinal studies to show. Like, for example, a researcher at the College of William & Mary has shown that over the last 20 years, creativity has declined in America among college students, which makes sense because all we do is teach to the test. There’s not a lot of divergent thinking going on sadly.

I think that it’s mixed. I think it’s a weird place that we’re in right now, socially and emotionally, because quarantine and masking is interesting in terms of helping people read people. I think social media has distracted people from building quality relationships. We know that it produces anxiety and stress and loneliness, depression. And so, I find it fascinating in that it feels like this burgeoning interest like never before, but yet the conditions that we’re all living in are like making it difficult for that interest to flourish.

And that’s why we need, myself included, at dinner— it’s like no freaking cell phones. It’s like I go to people’s… not now, but you know, people have the television on during dinner and their phones next to them. And there’s like little to no social interaction. Last year, I was on vacation in Panama, and we were at this hotel for lunch in a big family of like 10 people. Nobody was interacting. Everyone is on their phone. So it’s fascinating to me.

Denver: You talk to people after a power outage, and they say it’s some of the best three days they’ve had in a long, long time because they’ve talked to their family; they’ve done other things. They’ve read books. You get away from it, and you realize how much you’re missing. But then again, once the power goes back on, we go right back to the addiction again as where we were.

Finally, Marc, what’s next in the field of emotional intelligence, and what do you really think the impact of this past summer and all the events that occurred is going to have on your work going forward?

Marc: It’s funny that you asked that like, “What’s next?” It’s a big question that people ask. And I say, let’s ask, “How do we go deeper?” Because that’s what I think is next. I think that I’m kind of burnt out from these articles, like the two-second method for managing your feelings. You need more than two seconds. And I think that hopefully, and sadly, this crisis has brought to light the critical importance of pausing, reflecting, being self-aware, being socially aware, managing emotions, making good decisions about your health and wellness, as well as other people’s health and wellness.

I’m still blown away by…I know that the adolescent brain is not fully developed, but college students have the capacity to engage in social distancing. They know it. And yes, there are reasons biologically for them to break the rules…but I don’t know. I watch these television shows like America’s Got Talent and I see these 11-year-olds that have the self-control to sing a song and make responsible decisions and hold themselves on this stage. And I’m like, If they can do it, the college student can do it.”

Denver: I agree with you. And not to sound like an old man, but somebody was saying to me the other day, “Twenty-year-olds were storming the beach of Normandy.” It’s not that you’re twenty, and you’re completely irresponsible. This is a matter of life and death and the common good. Not just you, but everybody else. So, I’m with you on that.

Marc: I think what’s happened is that we have not supported their healthy development over time. I’d want to know the histories of these children’s family lives, I want to know the histories of their education system, and I want to know what have they learned from preschool all the way to high school. Because in the schools that I know that take our work seriously, the brains of these kids are completely different. Their problem-solving skills, their perspective-taking skills, their empathy is like nothing I’ve ever seen before.

I’m envious. I don’t have the same empathy as these kids because I’m the adult kind of inventor. I didn’t live it. These kids are living it every year of their lives until they go off to college and career, and just the neurons that are firing and the connections that they’ve made are not the ones that I have going on. And I’m, as I say, in many ways, envious of the kids who get the opportunity to learn these skills, and also I’ll say angry at the schools that deny children what I believe is that human right to learn these skills.

Denver: But also proud of the contribution that you’ve made. And just my closing thought on that would be it probably deals with a lot of those workplace issues, too, if you can teach these kids at school so by the time they get to the workplace, their full selves can show up, and not who’s excluded.

Marc: Correct. Although, importantly, this is life’s work. So, at 51 working from home, never worked from home before. While I’m enjoying it for the most part, I’m also sometimes ready to pull my hair out. As you can see, my hair keeps growing. And so, I’ve had new lessons in how to manage my anxiety. Life is going to have many ebbs and flows and ups and downs, but the more we can be prevention-focused and prepare our children, the easier it will be for them to adapt and learn and try new things in situations like this.

Denver: Absolutely. Well, Marc, thanks so much for being here today. The name of the book is Permission to Feel: Unlocking the Power of Emotions to Help our Kids, Ourselves, and our Society Thrive. And it’s now out in paperback, too.

Marc: That’s right.

Denver: It was a real pleasure to have you on the show, Marc.

Marc: I really appreciate it, Denver. Thank you.

Listen to more The Business of Giving episodes for free here. Subscribe to our podcast channel on Spotify to get notified of new episodes. You can also follow us on Twitter, Instagram, and on Facebook.