The following is a conversation between Ingrid Newkirk, Co-founder and President of PETA and Denver Frederick, Host of The Business of Giving on AM 970 The Answer WNYM in New York City.

Denver: People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, commonly known as PETA, will turn 40 years old this year. It is the largest animal rights group in the world, and its slogan is: Animals are not ours to eat, wear, experiment on, use for entertainment, or abuse in any other way. And it’s a pleasure to have with us this evening the Co-founder and President of PETA, Ingrid Newkirk , who has just come out with a new book titled Animalkind: Remarkable Discoveries about Animals and Revolutionary New Ways to Show Them Compassion.

Ingrid Newkirk, Co-Founder and President of PETA

Good evening, Ingrid, and welcome to The Business of Giving!

Ingrid: Thank you, Denver. Delighted to be here.

Denver: Speak about your underlying philosophy, the underlying philosophy of the organization that drives all of this work.

Ingrid: Well, I grew up like most people caring about animals, which meant you never beat the dog or starved the horse, and that was basically what it meant. I read a book by Peter Singer called Animal Liberation, which is often called the “Bible of the animal rights movement,” and it changed my way of thinking.

In his book, he says that perhaps you shouldn’t just be kind to animals, you should consider them as other nations or other tribes, that they are just forms of life like our own. You may look different, but everyone has a beating heart; everyone has emotions. They think. And so, perhaps they’re not ours to use at all. It’s not that you would have a longer chain or a bigger cage; it’s that perhaps they should just be left in peace and not ours to make into hamburgers and handbags and coats and so on.

Thinking of ourselves as basically gods and the rest of the animal kingdom as unimportant or even trash just really doesn’t fit with our idea of ourselves as intelligent, thinking people with compassion for all and respect, and who understand other cultures. Animals, after all, are just other cultures.

Denver: Yes. PETA has challenged the idea of human supremacy in the animal world, correct?

Ingrid: We have indeed. I grew up in the women’s rights movements, and the gay rights movement came after that, and the premise has always been that we shouldn’t be looking for our differences, we should be looking at our similarities. We should have great compassion for everyone, even if they don’t exactly fit the mold of ourselves.

And so, the same is true, the same principle applies. If racism is wrong, if sexism is wrong, human domination of any living being is wrong. So, thinking of ourselves as basically gods and the rest of the animal kingdom as unimportant or even trash just really doesn’t fit with our idea of ourselves as intelligent, thinking people with compassion for all and respect, and who understand other cultures. Animals, after all, are just other cultures.

Denver: Yes. Notwithstanding Peter Singer’s book, you were on your way to becoming a stockbroker. What happened that changed the trajectory of your life and got you to start PETA?

Ingrid: Well, I really just wanted to travel. I had traveled as a child all over, and I wanted to continue that as an adult. I was footloose and fancy-free, but I had to do something. I’ve always liked mathematics. I’ve always liked figures. And for some reason, I thought, “Well, I’ll study for the brokerage exam.” And that’s what I was doing. But in my heart, I knew I’m not a sales person. I’m not a person who really cares that much about money. I’m sorry to say that it wouldn’t have suited me.

And then someone next door to me, in the countryside in Maryland, moved away, left all these cats behind, and I found myself taking them to the shelter. When I got to the shelter, the conditions were so appalling. The place was so filthy; the people didn’t care at all; then I saw a little notice on the bulletin board for a kennel cleaner.

And so, I went to the front office and said, “May I apply?” And they said, “No. You’re overqualified,” which is something I’ve never understood. How can anyone be overqualified for anything? You can be underqualified, but you really can’t be over- qualified. And so, I fought for that job, and I got it, and I ended up helping reform that facility. And that was the start of my journey into animal welfare, animal protection, animal legislation, and ultimately, animal rights.

We started a movement to say: Fur is not desirable. It’s hideously cruel. It’s unnecessary. It’s a survivalist sort of clothing. You don’t need it.

Denver: Well, it’s been an incredible journey.

Let’s talk about some of this work. I think many listeners might be most familiar with PETA through your campaigns against wearing fur. What were some of the milestones of that effort? And by and large, how did wearing fur become socially unacceptable?

Ingrid: We started 40 years ago, and back then, fur was incredibly desirable. A little girl growing up would try on her mother’s or her grandmother’s coat, sometimes with fox tails and artificial eyes on the fox’s heads – all sorts of things. No one thought about it.

And then someone came up with a videotape – I think it was from Canada – of animals being caught in steel traps and absolutely bug-eyed, petrified. And we decided we would try to get all of the groups together to do a mailing to people, anyone we could find, and show them the photographs from this – it wasn’t a video back then, it was a film – show them stills from this film. And we started a movement to say: Fur is not desirable. It’s hideously cruel. It’s unnecessary. It’s a survivalist sort of clothing. You don’t need it. And it took off, but it took off very slowly.

Denver: Yes. It takes a while to get traction from these campaigns. It probably took what –5, 10 years, maybe? I don’t know.

Ingrid: Maybe more. Because I remember we were in New York, and we would actually have steel traps that we had padded and put on our own hands. We would crawl along the sidewalk outside fashion shows, and people would just laugh. We would have protests outside Bloomingdale’s and Macy’s and so on. Some people would be horrified, and others would just go right on into the fur seller.

But today, of course, we’ve pushed very hard, and we have never let up over these years. And now we have: Macy’s is closing its fur salon, as you know.

Denver: This past year. I saw that.

Ingrid: Yes. And Gucci, Galliano, Donatella Versace, Donna Karan – none of these people design and sell fur anymore. It’s over. The fur wars are basically over.

Denver: That one’s done, yes.

In Animalkind, you discussed some of the alternatives to fur. What are some of the best of these?

Ingrid: Well, it’s not just fur either. Some people are quite stunned to hear our undercover investigations, particularly in places like China and in Africa for crocodiles, but China for angora; badger hair, which is used in paint brushes and makeup brushes. All of these come from animals who don’t voluntarily give up their skin, or their wool, or whatever it is. They’re not saying, “Take me.” And so, it’s really barbaric how they’re treated.

When we’ve shown that to companies like H&M and Zara and so on, they’ve said, “All right, fine. We’ll take it off the shelves. We won’t sell it.” Zara is an incredibly ethical company, and they in fact gave us something like $1 million worth of angora they had in stock, which we then sent to refugee camps overseas for the winter in places like Afghanistan.

But yes, there are many alternatives, and you see people now making fibers out of – there’s pineapple leather, there’s apple leather, there’s grape leather, there’s faux fur, of course, galore. But you don’t have to have a synthetic. You can use one of the natural fibers like jute or hemp. It’s extraordinary what designers are doing these days with threads and natural materials.

Denver: Yes, the technology has come so far that alternatives are so much easier than they were four decades ago.

PETA is also known for its undercover investigations, and perhaps one of the earliest and most famous, was the Silver Spring monkeys. Tell us about that case.

Ingrid: That was quite an eye opener for people. And in fact, that really launched us because people didn’t realize you could do anything about what was happening to animals in laboratories. And most people, I think, honestly thought it’s just a few animals, and they’re being used; they’re being treated well, and they’re being used for lifesaving procedures.

We were able to show through the Silver Spring monkeys that there’s actually millions of animals that are kept abominably, and they’re used for every fool purpose under the sun.

Denver: Ends justify the means.

Ingrid: Exactly. And we were able to show through the Silver Spring monkeys that there’s actually millions of animals that are kept abominably, and they’re used for every fool purpose under the sun.

In the case of the Silver Spring monkeys, there were 17 macaque monkeys being kept in these small cages with broken wires – filthy, not cleaned – in a laboratory in Silver Spring that was actually just a warehouse. They were getting tons of money from the National Institutes of Health, all tax funds, and they had put out for grants from everything from the Red Cross to who knows what.

And what this experimenter would do – and this is not unusual that he didn’t have any medical training whatsoever (He wasn’t a veterinarian; he was a psychologist) – he would cut open the monkey’s backs. And then one or more of their arms would be what he called “deafferented.” They wouldn’t be able to feel as much. He would put them in a converted little refrigerator – the sort you keep coffee or something – and he would electroshock them to force them to stop the shocks by using their deafferented arms. It was just rubbish. He said it was to help people with strokes. And, of course, we went to medical authorities and stroke organizations, and they said, “Rubbish.”

So we were able to get a search warrant, take the animals out, put him on trial, and it was the front page of the Washington Post. It went all over the world. And suddenly, we had sacks and sacks of mail, and people saying those magic words, which are: “How can we help?”

Denver: That’s beautiful.

Ingrid: And we said, “Let’s tell you how you can help.”

Denver: We were ready for that question.

And now, they’re using synthetic frogs in biology class, correct?

Ingrid: We just paid $150,000 to make what’s called a “syn frog.” I’ve actually used it. It’s fascinating. It has a membrane, a skin that you can cut up, and its organs are inside. You can take them out with forceps just as you would with a real frog. And of course, not only is it cruel to frogs to use a real frog, it’s a stupid, old-fashioned lesson. Little boys like to dangle the frog’s innards in front of the little girls – don’t need it. Formaldehyde is used with a real frog – don’t need it with the synthetic frog. And so, children today can be more effective. They can learn much easier, and you don’t need the frog. So, we’re coming away from that.

Denver: That’s great.

Let’s go to sports and entertainment. Now, we all know about Barnum & Bailey and Ringling Brothers Circus. That is no longer the case. But I want to ask you about two other sports. One is the Iditarod, and that is the sled race for dogs in Alaska, and the other is horse racing. How do those campaigns stand at the moment?

Ingrid: Well, the Iditarod has got to go. This was started years and years ago for a good purpose, which was to bring medicine from one place in Alaska to another, and then it became a sort of sport, and now we have big purses offered to the winners. But so many dogs die. They die falling into crevasses. They die of pneumonia – that’s the most common thing. They have respiratory problems. Many of them are in awful shape during the race. They have veterinarians along the way to take some out.

But we did an undercover investigation, and we went to some of the kennels of even top winning Iditarod champs and found the way they keep their dogs when they’re not racing… which is out, staked in the ground by the cold ice, by the sea even, 17 to 30 degrees below zero, chained out with just a piece of wood, a box basically. They get no bedding on the ice, turning in circles for their whole lives. And then those, of course, who don’t make it in the race, are just disposed of.

So the Iditarod is a terrible throwback to a time when nobody realized who a dog is – that a dog is a social pack animal; that they don’t want to be deprived of proper food; that they need veterinary care and all these things.

So the Iditarod has got to go, and unfortunately, some sports person has just picked it up and wants to make it bigger than it is, and it should be fading out.

Denver: But on the other hand, Coca Cola has pulled their sponsorship from it, so it’s going both ways.

Ingrid: Indeed. Yes, and many people have too. Jim Beam, for example. I think as soon as you point out to the major companies that this is really a stain on their reputation – it’s nothing to be proud of; it’s nothing they want their banner put on – that many of them do withdraw.

Denver: Yes. And in horse racing, I guess so much attention has come from Santa Anita where so many horses have had to be put down. Where do you stand with that campaign?

Ingrid: We’ve been very busy. We work behind the scenes with a lot of the race track owners to appeal to them to please at least implement reforms. And that’s things like not using the whip, getting a proper track surface, and this is the big one – making sure that those horses are not running on drugs. And unfortunately, legal drugs and illegal drugs are rampant in the industry. We’ve seen it in other sports, but of course, in horse racing, it’s very much hidden because the horses are not going to say anything, and they’re not going to tell on the other horses.

But we have done undercover investigations. We’ve shown drugs like Lasix being given to the horses when they don’t have a problem, but simply as performance enhancers. And so, horse racing is a dirty business. There’s no question about it. We actually have a lawsuit now where we are helping a bettor, of all people, who placed a bet on a horse and lost. But afterwards, it was determined that the winner of the race was drugged up. So, of course, bettors don’t know where they stand either.

Denver: Let’s turn to meat, and PETA has been at the forefront of the vegan movement. You have your starter kits. I think you’ve sent out 300,000 or so just last year. And more and more people are going to a plant-based diet. And this is particularly true among Gen Z-ers that I’ve been able to observe.

Do you plan on continuing to inform and educate and get people to try vegan to see how they like it? Or do you think it might be a bit more forceful, as you have been in some of your other campaigns?

Ingrid: We’re a mixed bag. I think you’ve hit the nail on the head. We give out free food samples, particularly to the young, as you say. A lot of people are changing in the older bracket because they are worried about heart disease and cancer, and then people are changing because of the environment.

But the exposé is about animals, the cruel conditions on factory farms, in slaughterhouses. I just looked at a video last week that even I, looking at so many, found very, very hard to take. People see those and think, “Well, maybe it’s time.” The Golden Globes, as you know, just changed—

Denver: I saw. They changed everything on their meal just before Christmas – 1,300 vegan meals.

Ingrid: Yes. It’s fantastic. And they know they have an obligation really to go in that direction. Martha Stewart just came up with a very funny video advertising the Beyond sausage or meatballs for Subway. You’re seeing that Hardee’s has a Beyond burger, Dunkin Donut – it’s everywhere.

Denver: Burger King just came out with their Beyond sausage today.

Ingrid: Yes. It’s so exciting. But I think there are so many good reasons that we can have a carrot-and-a-stick approach is that we do need to nudge people – “Come on. It’s personal responsibility. You’re an ethical person.” Or “You’re worried about your health.” Or “You don’t want the planet to be destroyed by deforestation, the Amazon burning and so on.” But really, we were able to work with corporations very nicely and say, “You’re missing a huge market if you don’t put this on your menu.” And they do.

Denver: Yes. Well, that’s how it starts at least.

Ingrid: Well, KFC in Atlanta just tried “finger-lickin’ vegan chicken” as a test, and it sold out in five hours.

We are opportunists. We have to keep this very serious issue about the suffering of animals and the needless slaughter of animals in the news.

Denver: Fantastic. You know, you’re so well-known for your outrageous publicity stunts and these controversial campaigns, many of them which have gone viral. What have been some of the most effective? And what makes a campaign like that effective?

Ingrid: Well, that would be giving away our secrets, wouldn’t it?

Denver: That’s okay.

Ingrid: Well, we look at opportunities. We are opportunists. We have to keep this very serious issue about the suffering of animals and the needless slaughter of animals in the news. And as you know, we have heavy competition. We’re up against politics, conflict, sex, Good Lord knows what!

Denver: Hard for anyone to get noticed.

Ingrid: It is, and so sometimes we have to be extraordinarily gimmicky. One of the things we have done, of course, is we have sexy ads. And people, even if they disagree with what they think is sexual exploitation, they have to have a look.

Denver: There you go.

Ingrid: It’s like a car crash. You don’t like it, but you have to have a look. And so, we will do things that are quite provocative.

Denver: Such as?

Ingrid: Well, we had a SuperBowl commercial – it’s still online, you can go and see it – called “sexy veggies.” It’s women in lingerie at a steam bath who are holding various vegetables, and you read into it what she wants. We never shoot anything that’s totally nude, but people think it is. And so sexy things really do get—

Denver: Do we hear from women’s groups on that?

Ingrid: Yes. But I’m a feminist. I’ve marched. I’ve also stripped down. Don’t think too deeply about that because I’m 70 years old. But even 10 years ago, 5 years ago, I did naked marches when we had to. So, yes.

…the cute and fluffy ones usually go to the “no kill” or we refer them there. And they refer to us the dregs, if you will, the poor, broken ones, the ones who’ve been hit by a car and no one can afford, the ones who have cancer.

On our website, we have a video of our fieldworkers and our shelter, and I challenge anyone who criticizes us for euthanizing. Watch that video, and then tell me what you think because if we won’t take them in, no one will. And really, they need that final courtesy, that love, being held, being looked after in their final moments, and a painless exit from a world that doesn’t want them, or a world that they finished with.

Denver: One of the issues that is quite controversial is the organization’s stance on euthanasia. Why don’t you explain that, what it is, and your reasoning behind it; and particularly this has to do with your shelter in Norfolk, Virginia.

Ingrid: Yes. We have a shelter, what we call the “shelter of last resort” in Norfolk. And what is happening these days, the buzz phrase is no kill. And it does sound – I mean, who wants to kill animals? So, all these shelters know that they will get more funds and more attention and more sympathy if they are “no kill.” But what that is doing is a terrible thing.

To become no kill in a society where animals are thrown away, where there are still puppy mills, where animals are still breeding, and pet shops are still selling them, it means that when someone has an aged animal or an animal who is very aggressive and can’t be placed, these shelters won’t take them. So, the doors are closed.

These no kill shelters, also, by and large, they restrict their hours. So a working stiff who has an animal they can’t afford; maybe they’re unemployed … who knows what, they can’t afford to take to a veterinarian, and they’ve got to keep going to work because the vet may charge $200 for a euthanasia will come to us. We charge nothing. We’re open 24 hours a day, 365 days a week, and we will take in all comers.

So the cute and fluffy ones usually go to the “no kill” or we refer them there. And they refer to us the dregs, if you will, the poor, broken ones, the ones who’ve been hit by a car and no one can afford, the ones who have cancer.

On our website, we have a video of our fieldworkers and our shelter, and I challenge anyone who criticizes us for euthanizing. Watch that video, and then tell me what you think because if we won’t take them in, no one will. And really, they need that final courtesy, that love, being held, being looked after in their final moments, and a painless exit from a world that doesn’t want them, or a world that they finished with.

… it’s not exactly our most vigorous campaign, but it certainly is something we think is important because language is important.

It’s part of a little bit of a debasement that if you put into language things like: “There’s more than one way to skin a cat,” even “Take the bull by the horns,” which is bull- fighting and these bull wrestling things; it becomes something normal, and we want to get away from that.

Denver: Yes. That’s tough stuff.

Talk a little bit about language. There’s a lot of animalistic idioms out there that you’re trying to get out of the vernacular like: “There’s more than one way to skin a cat.” And also pets. You don’t like the idea of people calling their animal companions “pets.” Speak about all of that.

Ingrid: Well, it’s not exactly our most vigorous campaign, but it certainly is something we think is important because language is important.

Denver: You’re absolutely right.

Ingrid: And if you look back at… no one can say the “N-word” anymore. That’s marvelous. There are people who want to say it, but they know they can’t, and that’s progress. In the old women’s movement when we used to march and be called “bra burners” and what have you, it was, “Sweetie, will you bring me the coffee?” and wolf whistling and calling women “chicks” and so on.

It’s part of a little bit of a debasement that if you put into language things like: “There’s more than one way to skin a cat,” even “Take the bull by the horns,” which is bull-fighting and these bull wrestling things, it becomes something normal, and we want to get away from that. So we say, “Take the rose by the thorns” and not feed a bird – what is it?” Feed a bird two scones,” or whatever it is.

Denver: Kill two birds with one stone.

Ingrid: Yes. It’s: “Feed two birds with one scone.” So we have a little dictionary of idioms, so you can choose one that doesn’t disrespect animals. It’s fun, but it’s also got a good, solid point behind it.

Denver: Those must be fun brainstorming sessions down at your office as you’re coming up with the replacement idioms.

You were once regarded as an extremist fringe group, a radical voice, and now, with all the progress that has been made, PETA is in a little bit in danger of becoming mainstream. How does an organization keep its edge and face that complacency that can come about?

Ingrid: Don’t I know it! Yes, this is something we agonize about because on one hand, of course, it’s marvelous when a social cause movement is accepted. The things that were considered radical and revolutionary now have become mainstream ideas.

In the main, no pun, but you still see people walking down the street in Canada goose jackets, young people who know that fur is wrong, but haven’t really connected the dots and still have this bit of coyote fur around the neck. So, there’s a long way to go but, yes, we’re mainstream.

We talk about it all the time. We refocus things. We had a youth group that has been pretty much inspired to become more vigorous than it was. It was very – well, I would say it was becoming mainstream. It’s now going to be more agitating. But we talk about it, and we try to tweak things that we’re doing so that they do still get attention.

But you’re right, much of our work has gone behind the scenes with corporate meetings, influencing people in other ways, writing opinion pieces. This book, Animalkind, I consider it mainstream in a way, but also it does have revolutionary ways you can help animals in it. So yes, it’s a hard way to think of things.

Denver: I guess a big piece of it though is that you’re just self-aware of it, and doing that, you stay focused on it to try to keep that edge. And it happens with so many organizations; they don’t realize that they’ve become a little blunt, and you’re certainly aware of all of it.

Talk a little bit about that corporate culture down there. You have a reputation of being an exceptional place in which to work. Tell us what makes it special and distinctive to be an employee at PETA.

Ingrid: I’m extremely happy that we do have a very solid foundation of senior vice presidents. Some have come up from receptionist or somebody in the mail room, but they’ve shown their worth and they’ve put in their time, and it’s not just longevity, it’s interest and skill and talents. Mostly, it’s just the honest belief that what we’re doing is important. And so, they’ve come up, and they hold the fort. They also hold the history of the organization in their heads because they’ve been there 25-, 30 years, 34 years. Me, 40 years. Look at the crow’s feet.

Denver: You can’t use “crow’s feet” anymore, right?

Ingrid: I think you can actually. Then we have young people who these days – it’s everybody’s song of lament that young people today, it’s the same reason you can’t get a watchmaker whose grandfather and father and now, they are going to be a watchmaker for life, is that they want flexibility. So they may come in for a couple of years, and you hope to school them in that time, and then if they become interested in doing something else or moving on, you hope they’ll take their animal rights information and educate others wherever they go.

Denver: They become ambassadors.

Ingrid: Absolutely. Exactly. But now, our corporate culture is… We’re not IBM. We’re not Google. We don’t have childcare creches, and we don’t do your laundry for you, and we don’t pay you enough that you can buy a yacht. But we do try to keep our compensation at a decent level, and we look particularly at entry level as well. I think people who have been with us for a long time are sort of used to the fact that they’re not going to make big corporate salaries, and they’re not expecting it, whereas young people have higher expectations.

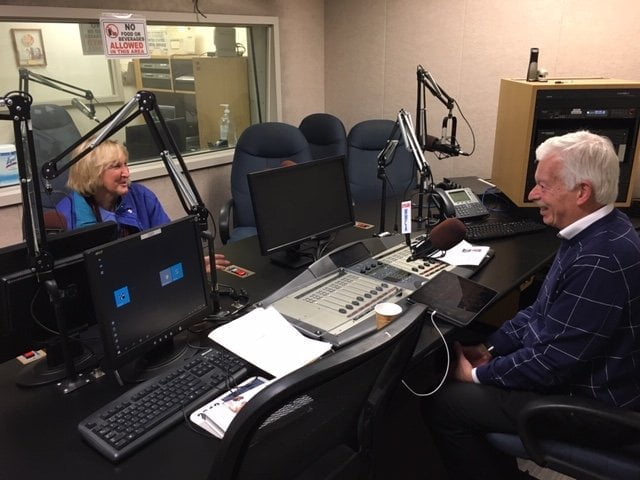

Ingrid Newkirk and Denver Frederick inside the studio

Denver: Yes. Well, they have meaning and they have purpose, and there’s always an offset in all these types of decisions that you make.

Let’s talk about Animalkind, which you co-authored with Gene Stone. And in it, you talk about animals’ intricate emotions, the way they communicate, their intelligence, their empathy, and so on. Share with us some of the revelations.

Ingrid: Well, I thought I knew a lot about animals, but in researching for this book, I found out some extraordinary things that I didn’t know. For example, and I’m not recommending this, if you take a snail away from his home, he will make his way back to it at the speed of 0.02 mile to 0.029 miles an hour, even if it takes him two years. I also found out that squirrels bury their cache of nuts by the position of the stars, and I had no idea of this. And if they see you watching them or another squirrel watching them, they’ll employ sleight of hand and actually pretend to bury a nut there, but not.

I was also fascinated by many things about elephants, some of which I knew, which, of course, is that they communicate by rumbling underground for one or two miles where they can communicate with another herd. And in fact, park rangers have found a herd of elephants up against the fence in a wildlife park just trembling and gathered together because another herd of elephants had told them through these rumbles that there was a cull going on, that people were shooting elephants in another part of the park.

They also have fascinating… they have more genes for smell than any other animal. So those trunks that you see are able to detect a scent at extraordinary ways. They also use the trunk as a snorkel when they swim, and they do swim. They’re excellent swimmers. They’ll plunge into the ocean and swim if they can – not, if they’re in the circus, poor things. They use their trunks the way we might use our finger and thumb, our forefinger and thumb to pick things up very delicately.

But every single animal from fish singing underwater to mice giggling – they actually giggle.

Denver: Chickens have a pecking order, don’t they?

Ingrid: They do. And, of course, not on factory farms, but they do have a pecking order. I just have an endless supply now of information, and I’ve tried to cram the most interesting parts into the book.

..it occurred to me that I could, if my body had managed to survive, I could will the bits and pieces of it to continue activism, so I drew up a will… if my body is still intact when I go, we’re going to use bits of it.

Denver: Well, you succeeded.

Let me close with this, Ingrid. You plan to continue your activism even after you die and have drawn up your will to ensure just that happens. What is that plan?

Ingrid: Well, I was almost in an air crash. Those of us on that plane who didn’t know we would live, we were all desperately thinking about things… about our family, our work, and so on. We did live, obviously, or I wouldn’t be here. But the next day, I was in a meeting and I thought, “What an awful thing that my activism, which is basically my whole life, the thing I want to do, would have been over.” And it occurred to me that I could, if my body had managed to survive, I could will the bits and pieces of it to continue activism, so I drew up a will. I have a pathologist. I have an attorney who can manage this, and if my body is still intact when I go, we’re going to use bits of it.

For example, part of my liver will be sent to France to protest foie gras, which is produced by force-feeding ducks and geese until their livers expand. It’s a hideous thing. My ear will go – at least one of them – will go to Canada, so perhaps presented to the Canadian parliament to say, “Can’t you hear the sounds made by the seals when they’re bludgeoned to death on the ice?” Maybe the seal kill will be over by then, and then we’ll find another use for the ear. But I’ve donated my body to PETA to use the bits and pieces; fry up the flesh with some onions and garlic, let people smell it, and come to see what they can eat. And then you say, “Oh Lord, it’s her. We’re all sisters under the skin.”

Denver: Well, I hope this doesn’t happen anytime soon.

Well, Ingrid Newkirk, the Co-founder and President of PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals) and the Co-author of Animalkind: Remarkable Discoveries about Animals and Revolutionary New Ways to Show Them Compassion, I want to thank you so much for being here this evening. How can people become more involved in the organization and help support this work if they’re so inclined?

Ingrid: Well, bless you for that question, Denver. We have, of course, websites and Twitter accounts, peta.org, and we want to help people make change. So, if someone has a child in school, or they’re a teacher, they’d like alternatives to dissection, resources are on the web of videos – happy ones, funny ones, very sad ones – are there to put on your social media account.

We have lists of cruelty-free clothing choices, lists of wonderful vegan foods, recipes, cookbooks – anything you want, we have. We’ll even mentor you. So please come and join us because we can’t have a kind world unless everyone gets involved… or a lot of people get involved, at least.

Denver: Well, thanks, Ingrid. It was a real pleasure to have you on the program.

Ingrid: Thank you.

Denver: I’ll be back with more of The Business of Giving right after this.

Ingrid Newkirk and Denver Frederick

The Business of Giving can be heard every Sunday evening between 6:00 p.m. and 7:00 p.m. Eastern on AM 970 The Answer in New York and on iHeartRadio. You can follow us @bizofgive on Twitter, @bizofgive on Instagram and at www.facebook.com/BusinessOfGiving